More Information

Submitted: October 19, 2023 | Approved: October 26, 2023 | Published: October 27, 2023

How to cite this article: Makunina NI. Fallow Lands of Tuva (Russia): 30 years of Steppe Demutation. J Plant Sci Phytopathol. 2023; 7: 113-117.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jpsp.1001115

Copyright License: © 2023 Makunina NI. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Virgin steppe; Secondary steppe; Old fallow; Demutation; Tuva

Fallow Lands of Tuva (Russia): 30 years of Steppe Demutation

Makunina NI*

Central Siberian Botanical Garden, SB RAS, 101, Zolotodolinskaya str., Novosibirsk, 630090, Russia

*Address for Correspondence: NI Makunina, Central Siberian Botanical Garden, SB RAS, 101, Zolotodolinskaya str., Novosibirsk, 630090, Russia, Email: [email protected]

Tuva has been a cattle-breeding region since ancient times, extremely continental climate of this region is little suitable for agriculture. However, the steppes of intermountain depressions in Tuva were heavily plowed by the early 1980s. In the 1990s most of the arable lands were abandoned; the process of restoration (demutation) of natural vegetation on fallow lands began. By now, 30 years later, the old fallows are expected to achieve the stage of the secondary steppe.

The purpose of this work is to estimate the differences between virgin steppes and corresponding secondary steppes in Tuva. Tussock, hummock, and desert virgin steppes have been compared with corresponding to three types of 30-year-old fallow communities. For this study, 330 geobotanical releves have been used. The criteria for comparison have been chosen as follows: the similarity of species composition, the spectrum of dominant species, species richness, grass cover, and grass height. The statistical validity of their differences has been verified. According to these criteria, virgin steppes and their 30-year-old fallow derivatives are shown to differ significantly.

The development of virgin lands in the 1960s marked a new period in agriculture of Russia and neighboring states: during several years, vast areas of virgin steppes were plowed [1]. In the early 1990s, a huge part of them was abandoned, so a large-scale natural experiment on arable land revegetation was triggered. Scientific works about its intermediate results [2-16] described fallows of different agricultural region. Fallows adjacent to Tuva agricultural areas of Baikal region [17], Krasnoyarsk Krai [18] and Khakassia [19-22] were delineated too.

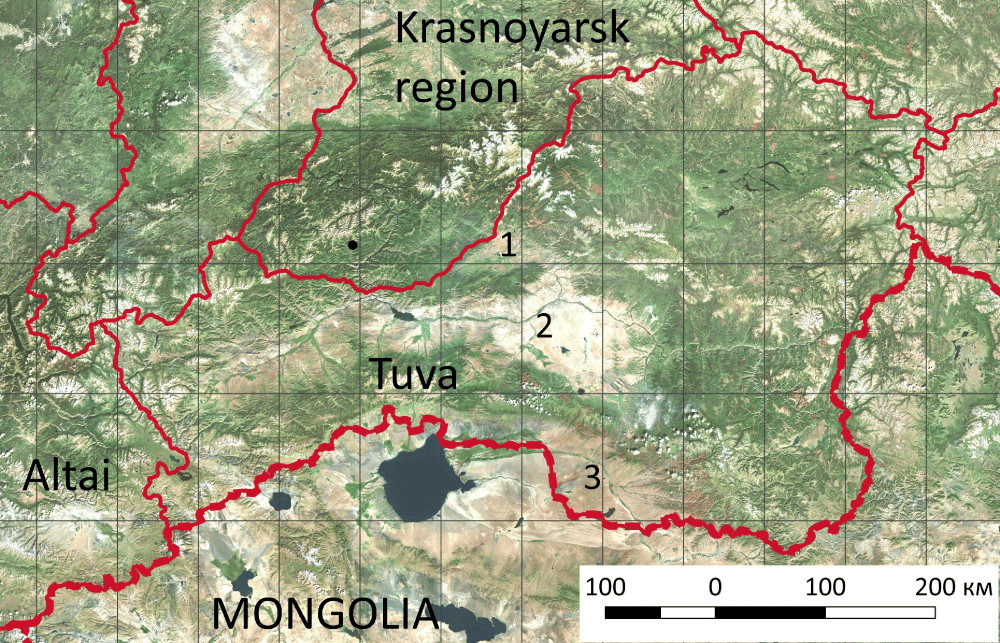

This article discusses the results of steppe demutation in Tuva, where until the 1960s cattle breeding predominated and arable lands were rare. Tyva is located in the center of the Eurasian continent; its length from West to East exceeds 700 km; from North to South it varies from 100 km in the West to 450 in the East (Figure 1). The extremely continental climate of Tuva is little suitable for agriculture. In winter, its territory is in the center of the Asian anticyclone. The stratification of cold air in intermountain depressions leads to air temperature decrease: the average temperature in January varies from -30 °C to -35 °C. The summer is warm enough: the average temperature in July fluctuates from +15 °C to +20 °C. In the northern Turan-Uyuk depression, 300 mm - 400 mm of precipitation falls per year, in Central Tuvan and Uvs-Nuur depressions the precipitation amount is reduced to 200 mm - 300 mm per year [23].

Nevertheless, by the early 1980s, the arable land area in Tuva amounted to 370.7 thousand hectares. The arable lands covered flat watersheds in 3 intermountain depressions: the northernmost Turan-Uyuk depression, where tussock steppes had prevailed before, and lying to the South Central Tuvan and Uvs-Nuur depressions coated with hummock steppe. Even desert steppes on gentle slopes at the foot of the ridges facing Central Tuvan and Uvs-Nuur depressions were partially plowed. In the 1990s, most of the arable lands in Tuva were abandoned. The 3 main trends of steppe demutation have been stated: the first one occurs on fallow lands in place of tussock steppes, the second one encompasses fallow lands in place of hummock steppes, and the third was noticed on fallow lands in place of desert steppes [24].

Demutation is characterized by different rates: it is fast in the initial stages but gets slow in the later ones [25]. According to A. M. Semenova-Tyan-Shanskaya's [26] process of steppe demutation can be divided into 4 stages. The initial, weedy stage continues from 1 to 5 years, and the intermediate, long–rooted one lasts for the next 5 years; after 10 years of succession, bunch grasses are supposed to dominate in fallow communities. This period is divided into two stages. From 10 to 20 years, tussock grasses predominate [27]; after a 20-year period, the stage of secondary steppes occurs: typical virgin steppes grasses are supposed to dominate [24]. By now, 30 years have passed since the start of steppe demutation in Tuva, according to the idea above, most fallow communities should be at the stage of secondary steppes.

The studies of Tuvan steppe fallows communities follow 2 main streams. The first one deals with an analysis of the productivity of different age fallows [28,29]. The second one encompasses the works on flora and phytocoenotic diversity of fallow communities [27,30-32]. Only some works compare Tuvan virgin steppes and fallows of different ages [24,33]; in these works list of dominant species and species richness have been chosen as criteria, but only a low number of samples have been analyzed. The comparison of other important phytocoenotic parameters (for example, grass height, and grass cover) has never been carried out, statistical validity of differences has never been verified.

The aim of this work is to measure the similarity of Tuvan virgin steppes and secondary steppes, i.e., 30-year-old fallows, using as criteria for comparing the spectrum of dominant species, species richness (average number of species on 100 m2), grass cover, and grass height. To verify the statistical validity of differences, quite a large number of geobotanical releves should be involved in processing. This work will check new criteria and will clarify some conclusions declared when analyzing individual samples.

330 geobotanical releves of the author, describing the virgin steppes and 30-year-old fallow communities of Tuva, have been selected. Each geobotanical releve contains a list of species and information about grass cover and grass height. The releves have been divided into 6 groups characterizing 3 types of virgin steppes and 3 types corresponding to them of 30-year-old fallows (secondary steppes). Virgin steppes form the following ecological series: tussock steppes are the most humid, hummock steppes take the central place, and desert steppes are the driest. When comparing virgin steppes and corresponding fallow communities, the species richness, grass cover, grass height, and dominant species spectra of each pair have been analyzed, validity of differences has been verified. When comparing coenoflora, the Jacquard similarity coefficient has been used. Statistical processing and calculation of the similarity coefficient have been carried out in the program PAST [34]. The scheme map of Tuva has been designed in the NextGIS QGIS version 18.10.0 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Scheme map of Tuva. Notes: 1 – Turan-Uyuk depression, 2 – Central Tuvan depression, 3 – Uvs-Nuur depression.

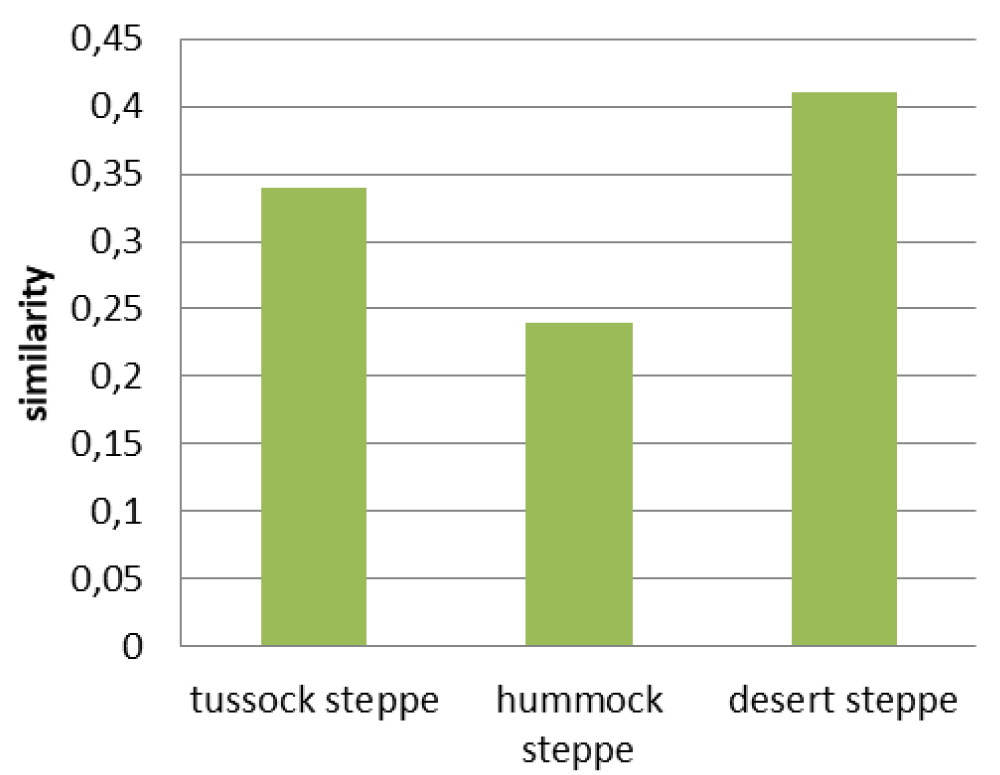

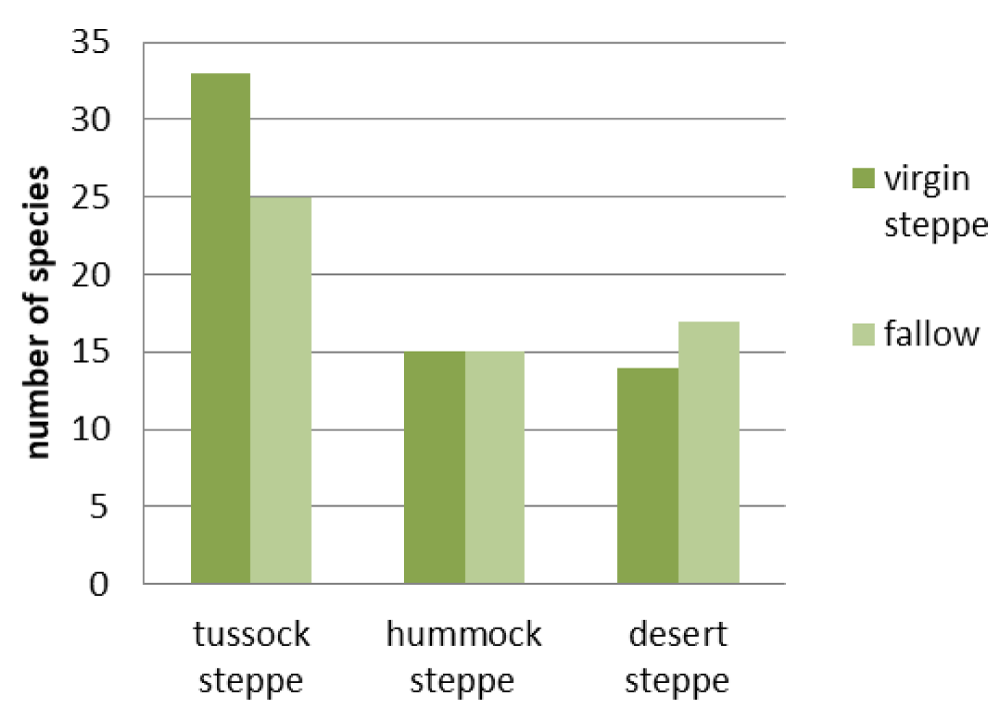

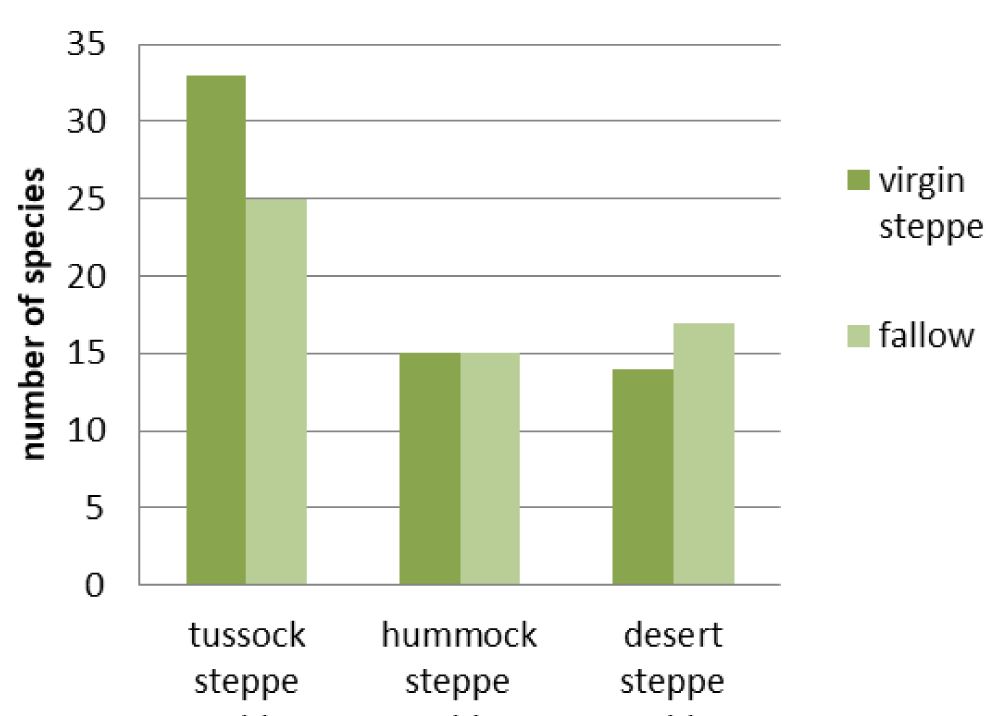

Virgin desert steppes and corresponding to them the fallow communities are the most floristically similar: the similarity index is 0.41 (Figure 2). They do not have statistically valid differences in either the grass cover or the grass height (Figures 3,4). However, the difference in species richness of this pair is statistically valid (p < 0.05) (Figure 5). Their appearance is different. In virgin desert steppes, the semi-shrub Nanophyton grubovii dominates, and the steppe herb Artemisia frigida is abundant (Table 1). Weeds Artemisia scoparia, Neopallasia pectinata, and steppe herb Artemisia frigida form the habitus of fallows. The floristic similarity is achieved through common subdominant species: Agropyron cristatum, Potentilla acaulis, and Stipa krylovii.

Figure 2: Similarity of different types of virgin steppes and 30-year-old fallows.

Figure 3: Species richness of different types of virgin steppes and 30-year-old fallows.

Figure 4: Grass cover of different types of virgin steppes and 30-year-old fallows.

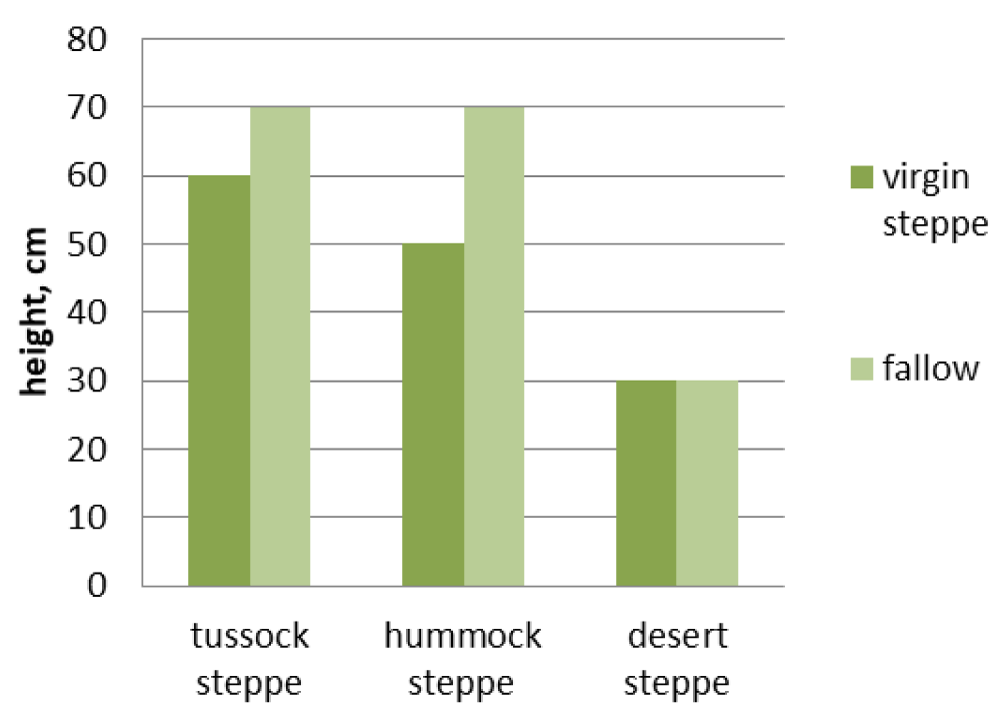

Figure 5: Grass height of different types of virgin steppes and 30-year-old fallows.

| Table 1: Dominant and subdominant species in Tuvan virgin steppes and its fallow derivatives. | ||||||

| Species | Desert Steppes | Hummock Steppes | Tussock Steppes | |||

| Virgin | Fallow | Virgin | Fallow | Virgin | Fallow | |

| Desert Steppe Species | ||||||

| Nanophyton grubovii | ++ | + | ||||

| Psathyrostachys juncea | + | |||||

| Stipa glareosa | + | |||||

| Hummock Steppe Species | ||||||

| Agropyron cristatum | + | + | ++ | |||

| Artemisia frigida | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ||

| Artemisia obtusiloba | + | + | ||||

| Cleistogenes squarrosa | + | + | ||||

| Kochia prostrata | + | + | ||||

| Koeleria cristata | + | + | ||||

| Potentilla acaulis | + | + | ++ | |||

| Stipa krylovii | + | + | ++ | |||

| Steppe Weeds | ||||||

| Artemisia scoparia | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||

| Artemisia sieversiana | + | + | ||||

| Heteropappus altaicus | + | + | + | |||

| Neopallasia pectinata | ++ | |||||

| Potentilla bifurca | + | + | + | |||

| Tussock Steppe Grasses | ||||||

| Achnatherum sibiricum | + | ++ | ||||

| Helictotrichon altaicum | ++ | |||||

| Leymus dasystachys | + | |||||

| Poa botryoides | + | ++ | ++ | |||

| Stipa capillata | ++ | ++ | + | |||

| Stipa pennata | ++ | |||||

| Meadow Grasses | ||||||

| Elytrigia repens | ++ | |||||

| Poa angustifolia | ++ | |||||

| Bromopsis inermis | + | |||||

| Other Steppe Species | ||||||

| Artemisia glauca | + | + | + | |||

| Carex pediformis | ++ | |||||

| Coluria geoides | + | |||||

| Festuca valesiaca | + | |||||

| Galatella angustissima | + | |||||

| Galium verum | + | + | ||||

| Medicago falcata | + | + | ||||

| Phleum phleoides | + | + | ||||

| Phlomoides tuberosa | + | |||||

| Potentilla longifolia | + | + | ||||

| Pulsatilla patens | + | |||||

| Scabiosa ochroleuca | ++ | |||||

| Schizonepeta multifida | + | |||||

| Veronica incana | + | + | ||||

| Notes: ++ - dominant species, + - subdominant species. | ||||||

Hummock steppes and fallows in their place have the lowest similarity index: 0.24 (Figure 2). The differences of this pair in grass cover and grass height were revealed to be statistically valid (p < 0.01) (Figures 3,4), but species richness is the same (Figure 5). Their appearance is very different: the virgin hummock steppes are dominated by steppe hummock species: Agropyron cristatum, Stipa krylovii, Artemisia frigida, and Potentilla acaulis, while tussock grasses Stipa capillata and Achnatherum sibiricum predominate in fallow communities (Table 1).

The index of floristic similarity of virgin tussock steppes and fallow communities in their place is 0.34 (Figure 2). Their differences in the species richness, grass cover, and grass height were found to be statistically valid (p < 0.05) (Figures 3-5). This pair has only one common dominant: tussock grass Poa botryoides. Steppe tussock grasses Helictotrichon altaicum, Stipa capillata, S. pennata, and Carex pediformis prevail in the virgin tussock steppes, while meadow grasses Elytrigia repens, Poa angustifolia, weed Artemisia scoparia, and Scabiosa ochroleuca dominate in fallow communities (Table 1).

According to the obtained results, the Tuvan virgin steppes follow general ecological patterns of dry communities: the wetter the habitat, the greater the number of species, grass height, and grass cover. Fallow communities mainly follow it too; the only exception is the high species richness of fallow communities in place of desert steppes.

When comparing virgin steppes and their fallow derivatives, such differences in their phytocoenotic characteristics should be noted: the grass height of virgin steppes is smaller, whereas the grass cover is higher. This trend is true for tussock and hummock steppe, it fades in desert steppes.

Two articles with comparisons of virgin Tuvan steppes and fallow in their place have been published. The article by A. D. Sambuu [32] presents the similarity indexes of virgin steppes and their fallow derivatives. The same trends have been noted in this article: virgin desert steppes and their fallow derivatives have maximal similarity index values, but the values are higher than the ones in this article. This fact can be explained by methodological approach differences.

In the article by A. A. Titlyanova and A. D. Sambuu [24], the prevalence of virgin steppe species in the secondary ones and similar dominant species spectra of virgin and secondary steppes have been declared. The first suggestion has been partly confirmed; the second one does not fully correspond to this article's results: the dominant species of virgin steppes and their 30-year-old fallow derivatives (secondary steppes) differ significantly [35,36].

The 30-year-old fallows (so-called secondary steppes) were considered to have the main characteristics of virgin steppe: similar dominant species spectra, similar species composition, and similar phytocoenotic characteristics. The results above make the fact obvious: virgin steppes and their 30-year-old fallow derivatives differ significantly. Their floristic similarity indexes are low, and most of the phytocoenotic characteristics differ validly.

This work was partially funded by RFFI with grant numbers: 19-29-05208/19 and 19-29-05209.

- Frühauf M, Meinel T, Schmidt G. The virgin lands campaign (1954–1963) Until the breakdown of the Former Soviet Union (FSU): with special focus on Western Siberia. In Frühauf M, Guggenberger G, Meinel T, Theesfeld I, Lentz S. (eds) KULUNDA: climate-smart agriculture. Innovations in landscape research. Springer. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15927-6_8.

- Ioffe G, Nefedova T, Zaslavsky I. From spatial continuity to fragmentation: the case of Russian farming. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2004; 94:913–943. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467–8306.2004.00441.x

- Henebry GM. Global change: Carbon in idle croplands. Nature. 2009 Feb 26;457(7233):1089-90. doi: 10.1038/4571089a. PMID: 19242461.

- Kamp J. Land management: Weighing up reuse of Soviet croplands. Nature. 2014 Jan 23;505(7484):483. doi: 10.1038/505483d. PMID: 24451529.

- Kraemer R, Prishchepov AV, Müller D, Kuemmerle T, Radeloff VC, Dara A, Terekhov A, Frühauf M. Long-term agricultural land-cover change and potential for cropland expansion in the former Virgin Lands area of Kazakhstan. Environmental Research Letters. 2015; 10(5):054012. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748–9326/10/5/054012

- Cherepanov SK. The structure of plant communities of fallow land in the system of protective forest plantations in dry steppes. Arid ecosystems. 2016; 22(1):85.

- Kholboeva SA. Flora and vegetation of the fallows of the valley of the Chikoi River (Western Transbaikalia). In Problems of studying of the vegetation cover of Siberia. Tomsk State University Publishing House. 2017.

- Lesiv M, Schepaschenko D, Moltchanova E, Bun R, Dürauer M, Prishchepov AV, Schierhorn F, Estel S, Kuemmerle T, Alcántara C, Kussul N, Shchepashchenko M, Kutovaya O, Martynenko O, Karminov V, Shvidenko A, Havlik P, Kraxner F, See L, Fritz S. Spatial distribution of arable and abandoned land across former Soviet Union countries. Sci Data. 2018 Apr 3; 5:180056. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.56. PMID: 29611843; PMCID: PMC5881411.

- Atutova ZV. The current state of fallow lands in the Tunka depression (Southwestern Cisbaikalia). Geography and Natural Resources. 2020; 41:141-150.

- Azarenko MA, Kazeev KS, Yermolayeva OY, Kolesnikov SI. Changes in the plant cover and biological properties of chernozems in the postagrogenic period. Eurasian Soil Science. 2020; 53:1645-1654.

- Levykin SV, Chibilev AA, Kochurov BI, Kazachkov GV. Towards a strategy for the conservation and restoration of steppes and environmental management in the post-virgin land space. Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Geographical series. 2020; 84(4):626-636.

- Levykin SV, Chibilev AA, Ulyanov YA, Kazachkov GV, Yakovlev IG, Nurushev MZ. The virgin land mega project and the land reform as the global experiment of steppe self-restoration in North Eurasia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021; 817(1):012058.

- Novikova LA. Demutation of meadow steppes of the Volga upland in protected conditions. Samara Scientific Bulletin. 2020; 9(3):100-106.

- Tokhtar VK, Zelenkova VN. Classification of flora of agrophytocenoses growing in the southwest of the Central Russian Upland (Russia). Plant Cell Biotechnology and Molecular Biology. 2020; 78-85.

- Volkova EM, Rozova IV. Diversity of vegetation on the fallows of Kulikov field (Tula region). Bulletin of Tula State University. Natural Sciences. 2020; 3:12-26.

- Pazur R, Prishchepov AV, Myachina K, Verburg PH, Levykin S, Ponkina EV, Kazachkov G, Yakovlev I, Akhmetov R, Rogova N, Bürgi M. Restoring steppe landscapes: patterns, drivers, and implications in Russia’s steppes. Landscape ecology. 2021; 36:407-425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01174-7

- Kazanovsky SG, Dorofeev NV, Zorina S Yu, Sokolova LG. Vegetation of fallow of different ages in the forest-steppe zone of the Baikal region. Problems of Botany of Southern Siberia and Mongolia. 2022; 21(2):54-58.

- Botvich I, Pisman T, Kononova N, Shevyrnogov A. Seasonal dynamics of fallow land vegetation in Krasnoyarsk forest-steppe according to ground and satellite data. Issledovanie Zemli iz kosmosa. 2018; 6:39-51.

- Kutkina NV, Eremina IG. Bioclimatic potential of fallow lands of Khakassia. Agrarian science. 2018; 11-12:66-69.

- Kutkina NV, Eremina IG. Demutation and bioproductivity of the fallow in the conditions of the hilly steppe of Khakassia. Bulletin of the Krasnoyarsk State Agrarian University. 2021; 10(175):3-10.

- Botvich IYu, Zorkina TM. Dynamics of vegetation restoration of fallows in the steppe zone of the Republic of Khakassia according to ground and satellite data. Biophysics. 2019; 64(2):409-416.

- Kutkina NV. Restoration of fallow lands in the conditions of the steppe catena of Khakassia. Scientific Life. 2019; 14(10):1584.

- Bakhtin NP. Climate features and agro-climatic resources of Tuva ASSR. Collection of scientific works of the Krasnoyarsk Hydrometeorol. Observatories. 1968; 1:26-68.

- Tiplianova AA, Sambuu AD. [Determinacy and synchronicity of fallow succession in the Tuva steppes]. Izv Akad Nauk Ser Biol. 2014 Nov-Dec;(6):621-30. Russian. PMID: 25739311.

- Gareeva SA, Khusainov AF, Tagirova OV, Giniyatullin RH, Kulagin AYu. Transformation of the vegetation cover of fallows in the vicinity of the natural park "Kandry-Kul" (Republic of Bashkortostan). Agrarian Russia. 2022; 9:34-40.

- Semenova-Tyan-Shanskaya AM. Restoration of vegetation on steppe fallows in connection with the question of the "passage" of species. Bot. journal. 1953; 6:862-873.

- Oorzhak AV, Kuular MM, Namzalov BB, Dubrovskiy NG. Fallow vegetation of Tuva (flora, phytocenology, structural and functional organization). Kyzyl: Tuva State University Publishing House. 2018.

- Titlyanova AA, Sambuu AD. Succession in grasslands. Novosibirsk: SB of RAS Publishing House. 2016.

- Makunina NI, Sambuu AD. Structure and stock of phytomass as indicators of the stage of demutation of steppe fallow lands in Tyva. Russian Journal of Ecology. 2022; 53(5):357-365. https://doi.org/10.1134/S106741362205006X

- Kuminova AV. Weed, fallow, and garbage vegetation. In Vegetation cover and natural forage lands of the Tuva ASSR. Novosibirsk: Nauka Publishing House. 1985.

- Dubrovskiy NG, Oorzhak AV, Namzalov BB. Steppes and abandoned lands of Tuva. Kyzyl: Tuva State University Publishing House. 2014.

- Dubrovsky NG, Namzalov BTs. B, Oorzhak AV, Kuular MM. Floristic-geobotanical and bioecological studies of the fallow vegetation of Tuva. Bulletin of Buryat State University. Biology. Geography. 2018; 1:27-43.

- Sambuu AD. Secondary successions of phytocenoses in steppe ecosystems of Tuva. 2022.

- Hammer Ø. PAST: Paleontological Statistics, Version 3.0. Natural History Museum University of Oslo. 2013.

- Guo X, Cui X, Li H. Effects of fillers combined with biosorbents on nutrient and heavy metal removal from biogas slurry in constructed wetlands. Sci Total Environ. 2020 Feb 10; 703:134788. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134788. Epub 2019 Nov 3. PMID: 31733500.

- Elith J, Leathwick JR. Species distribution models: ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annual Rev. Ecol. Evol. Systematics. 2009; 40(1):677–697. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120159