More Information

Submitted: June 21, 2022 | Approved: November 14, 2022 | Published: November 15, 2022

How to cite this article: Kwon-Ndung EH, Terna TP, Goler EE, Obande G. Post-harvest assessment of infectious fruit rot on selected fruits in Lafia, Nasarawa State Nigeria. J Plant Sci Phytopathol. 2022; 6: 154-160.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jpsp.1001090

Copyright License: © 2022 Kwon-Ndung EH, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Post-harvest; Pathogenicity; Fruits; Biocontrol

Post-harvest assessment of infectious fruit rot on selected fruits in Lafia, Nasarawa State Nigeria

EH Kwon-Ndung1*, TP Terna1, EE Goler1 and G Obande2

1Department of Plant Science and Biotechnology, Federal University of Lafia, Nigeria

2Department of Microbiology, Federal University of Lafia, Nigeria

*Address for Correspondence: EH Kwon-Ndung, Department of Plant Science and Biotechnology, Federal University of Lafia, Nigeria, Email: [email protected]

The post-harvest health and microbial safety of plant products and foods continue to be a global concern to farmers, consumers, regulatory agencies and food industries. A study was carried out to evaluate the pathogenicity of fungi associated with post-harvest rot of oranges, watermelons and bananas in Lafia, Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Healthy fruits inoculated with fungal spores obtained from rotted fruit tissues were incubated at ambient temperature conditions and observed daily for the appearance and development of tissue rot. Oranges and Watermelons had the highest number of fungal isolates (3) compared to banana (2). Fungi belonging to the genus Curvularia were the most isolated (37.50%), followed by both Aspergillus and Colletotrichum (25.00% respectively) and lastly Alternaria (12.50%). The highest tissue rot diameter of sweet orange (2.40 cm) was induced by Alternaria sp. followed by Curvularia geniculate (1.40 cm) and lastly Colletotrichum sp. (1.28 cm). The highest rot of banana fruit tissues was produced by A. niger (3.90 cm), followed by Curvularia geniculate (3.40 cm). Aspergillus sp. produced the highest tissue rot diameter on watermelon fruits (1.93 cm), followed by Colletotrichum sp. (1.30 cm) and lastly Curvularia geniculate (1.20 cm). Differences in the susceptibilities of different fruits to rot by fungal pathogens were significant (p ≤ 0.05). There is need for improved handling of fruits after harvest to prevent losses due to bacterial and fungal rots in the study area.

Infections from pathogens such as bacteria and fungi are the main causes of postharvest rots of fresh fruits and vegetables during storage, transport and cause significant economic losses in the commercialization phase [1,2]. Infections caused during postharvest conditions lower the shelf life and adversely affect the market value of fruits [3]. Contamination of fruits with microbial toxins does not only account for various health hazards but also results in economic losses, especially for exporting countries [2,4,5].

In Nigeria, cultivation of fruit crops and vegetables is prominent in the North-Central Region where the soils are well drained and rainfall is sufficient for efficient growth and reproduction of a number of fruit crops and vegetables. However, after harvest and storage, the post-harvest phase from the farm gate to major market outlets within and outside the country is often faced with challenges of microbial rots leading to substantive crop losses [6].

Fruit rots caused by fungal and bacterial pathogens result to huge annual losses during storage and transportation of harvested fruits in the study area. Identifying the rot causing organisms is crucial in the mitigation of post-harvest yield losses in the study area.

Citrus (Citrus sinesis L.) which originated from south-eastern Asia, China and the east of Indian Archipelago from at least 2000 BC [7-9] is one of the most important fruit crops known by humans since antiquity and is a good source of vitamin “C” with high anti-oxidant potential [10]. About 50% of the harvested crop is lost on transit in developing countries [11] and therefore development and use of alternative postharvest control options involving biological agents are critically important [12-15]. Moreover, natural plant extracts may provide an environmentally safer, cheaper and more acceptable disease control approach [16-18].

Banana is also one of the oldest fruits known to mankind. Its antiquity can be traced back to the Garden of Paradise where Eve was said to have used its leaves to cover her modesty. According to [19], banana is essentially a humid tropical plant, coming up well in regions with a temperature range of 10 °C to 40 °C and an average of 23 °C. In cooler climate, the duration is extended, sucker production is affected, and bunches are smaller. Low temperatures (less than 10 °C) are unsuitable since they lead to a condition called choke or impeded inflorescence and bunch development. In their study [20] reported that bananas require a fairly humid climate, moist deep rich soil with perfect drainage, protection from wind, full sun and much heat. For successful growth, banana demands plenty of warmth and moisture in the air throughout the year. Heavy rainfall and high temperatures which vary little throughout the year are suitable for bananas. The two most important diseases of bananas are Panama disease and leaf spot [19].

The watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) is a flowering plant that originated in North East Africa, where it is found growing wild [21]. It has sometimes been considered to be a wild ancestor of the watermelon; its native range extends from north and West Africa to west India. Evidence of the cultivation of both C. lanatus and C. colocynthis in the Nile Valley has been found from the second millennium BC onward, and seeds of both species have been found at Twelfth Dynasty sites and in the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun [22].

Citrullus lanatus is a plant species in the family Cucurbitaceae, a vine-like (scrambler and trailer) flowering plant originally from Africa. It is cultivated for its fruit. Watermelon fruit is 91% water, contains 6% sugars, and is low in fat. In a 100 gram serving, watermelon fruit supplies 30 calories and low amounts of essential nutrients. Only vitamin C is present in appreciable content at 10% of the daily value. Watermelon pulp contains carotenoids, including lycopene [23]. The amino acid citrulline is produced in watermelon rind [24].

Watermelon is rich in carotenoids. Some of the carotenoids in watermelon include lycopene, phytofluene, phytoene, beta-carotene, lutein, and neurosporene. Lycopene makes up the majority of the carotenoids in watermelon.

Different approaches have been used to prevent, mitigate or control plant diseases. Beyond good agronomic and horticultural practices, growers have often relied heavily on chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Such inputs to agriculture have contributed significantly to the spectacular improvements in crop productivity and quality over the past 100 years [25,26]. However, increasing use of chemical inputs has caused several negative effects, ranging from the development of pathogen resistance to the applied agents to their non-target environmental impacts. The growing cost of pesticides, particularly in less-affluent regions of the world, and consumer demand for pesticide-free food has as also called for a search for substitutes to these products. There are also a number of fastidious diseases for which chemical solutions are few, ineffective, or non-existent [25,27,28]. Today, apart from the strict regulations on chemical pesticide use and increasing political pressure to remove the most hazardous chemicals from the market, the spread of plant diseases in natural ecosystems may preclude successful application of chemicals, because of the scale to which such application might have to be applied.

In attempt to tackle the growing challenge of pesticide hazards, pest management researchers have focused their efforts on developing alternative inputs to synthetic chemicals for controlling pests and diseases. Among these alternatives are those referred to as biological controls [29].

The study was carried out in Lafia, Nasarawa State, Nigeria located on 8032’N 8018’E in the Southern Guinea Savannah region of North-Central Nigeria. It is home to abundant fruit crops such as Mangifera indica (Mango), Anacadium occidentale (Cashew), Citrus sinensis (Sweet orange), and Musa acuminate [30].

Healthy fruit samples (not showing visible signs of rot) of Sweet orange, Mango and Banana were obtained from Lafia Main Market and refrigerated in the Plant Science and Biotechnology Laboratory of Federal University of Lafia, at 4 0C prior to pathogenicity tests.

The rotted fruit samples were collected from retailers and merchants of the fruit products in different locations within Lafia metropolis, namely; Mararaba-Akunza (In the South), Lafia Main Market (In the East), Bukan-Sidi (In the North) and New Tomato Market (In the West). Sampled fruits were conveyed in sterile polyethylene bags to the Laboratory of Federal University of Lafia, for further processing.

For the isolation of fungi, partially rotted fruits were cut at intersections between rotten and healthy portions into smaller pieces (2 cm × 2 cm), surface sterilized by soaking in 5% Sodium Hypochlorite solution for 2 minutes. Three surface sterilized tissues each of plant materials collected from different locations were plated separately on sterile solidified Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) and incubated at room temperature (28 °C ± 2 °C) for 4 days. Pure cultures obtained were identified on the basis of spore characteristics and nature of mycelia, using a compound microscope and taxonomic keys [31].

For bacterial isolation, the method described by the International Commission on Microbiological Specification of Food [32] was employed as follows:

Each diseased fruit was first surface sterilized by mopping the entire surface with cotton wool moistened with 1% sodium hypochlorite solution (bleach). The disinfected fruits were further cut open with a flamed knife to reveal boundary areas between diseased and healthy portions. Smaller pieces of about 2 cm2 were cut and teased out in 10 ml of sterile water in a beaker. A loopful of the inoculum was subsequently collected from the suspension and aseptically inoculated evenly and streaked onto sterile nutrient agar plates. The inoculated plates were kept in the incubator at 37 oC for 48 hr and observed daily for colony growth. Singly formed colonies were collected and transferred aseptically onto sterile nutrient agar plates and incubated as earlier stated. Pure cultures obtained were used for further identification and subsequent tests.

The characterization and identification of bacterial isolates was based on macroscopic and microscopic examination of growth features as well as biochemical reaction tests, as enumerated below by [33-35].

Gram stain

Bacteria smear were heat-fixed and flooded with crystal violet on glass slides for one minute, after which the primary stain was washed off with water. The heat-fixed smear was further flooded with iodine for one minute and washed off with water. This was followed by flooding the smear with 95% alcohol for 10 seconds and safranin for one minute. Flooded smears were again washed off with water, air dried and observed for either the presence of a purple colouration as an indication of the presence of Gram-positive bacteria, or pink colouration for Gram-negative bacteria.

Catalase test

A sterile wire loop was used to transfer a small amount of colony onto the surface of a clean dry glass slide, after which a drop of 3% H2O2 was added. Evolution of oxygen bubbles was regarded as a positive result.

Oxidase test

A bacterial colony was picked with a sterile wire loop and smeared onto a filter paper soaked with the substrate (tetramethyl-p-phenylenediaminedihydrochloride) and moi-stened with sterile distilled water. The inoculated area was observed for a colour change to deep blue or purple within 10 – 30 seconds.

Indole test

The test organism was inoculated into Tryptone broth and incubated for 18 to 24 hours at 37 oC. Fifteen drops of Kovacs reagent were then added down the inner wall of the tube and observed for the presence of a bright red colour at the interface as an indication of the presence of indole.

Triple sugar iron test

The organism to be tested was inoculated into Triple sugar iron agar and incubated for 18 to 24 hours at 37 oC. After incubation it was observed for red slant, yellow butt, hydrogen sulphide production and gas production.

The pathogenicity of fungi isolated from diseased fruit tissues was determined using the method reported by [36] as follows:

Healthy fruits surface sterilized by swabbing with 5% Sodium hypochlorite solution were aseptically wounded by the removal of 7 mm diameter flesh tissue to a depth of 3 mm, with the aid of a sterile 7 mm diameter cork borer.

Seven milliliter (7 mm) agar discs obtained from actively growing mycelial regions of 7 days old cultures of potential rot fungi were aseptically plugged into wounded spots and incubated for 5 days at 28 oC. Artificially inoculated fruits were observed every 48 to 72 hours for the development of rot symptoms. Rot diameters were measured in millimeters (mm) with the aid of a meter rule.

The ability of bacterial isolates to cause rot in healthy fruit tissues was evaluated using the methods of [37]. Surface sterilization was carried out by swabbing entire fruit surfaces with cotton wool moistened with 1% sodium hypochlorite solution. Holes bored into fruit surfaces with the aid of a flamed 5 mm cork borer were aseptically inoculated with 0.5 ml of 48 hr old cultures of bacterial isolates, and covered by replacing the removed fleshy core and finally sealed sterile petroleum jelly. The inoculated fruits were labeled accordingly, kept at room temperature and observed daily for appearance of symptoms such as rot like colour change, softening, characteristic and foul odour. A control experiment was set up by opening and closing the core in fruits without introducing any organism except 0.5 ml sterile water. Inoculated fruits were examined two weeks after inoculation, and rot diameters were measured in millimeters (mm) with the aid of a meter rule.

Treatments were administered in a Completely Randomi-zed Design (CRD) with 3 replicates in a 3 × 5 × 2 layout in the laboratory. Data obtained from the treatments were subjected to Analysis of variance (ANOVA) at 5% level of probability.

Biochemical identification of bacteria associated with rotted fruits in Lafia

Results of the biochemical identification of bacteria associated with rotted fruits in Lafia are presented in Table 1. Banana had the highest number of bacterial colonies [4], followed by both watermelon and sweet orange (3 each). Bacteria belonging to the genus Streptococcus had the highest occurrence on sampled fruits (40.0%), followed by Staphylococcus (20%). Proteus, Micrococcus, Enterobacter and Bacillus all had 10.00% occurrences respectively on the sampled fruits.

| Table 1: Biochemical identification of bacteria associated with rotted fruits in Lafia. | |||||||||

| S/N | Isolate Code | Source | Micromorphology | Gram Stain | Catalase Test | Indole Test | Citrate Test | Triple Sugar Ion | Suspected Organisms |

| 1 | B1 | Banana | Diplococci | + | -weak | - | + | K/K | Streptococcus sp. |

| 2 | B2 | Banana | Cocci | + | -weak | - | + | K/K | Streptococcus sp. |

| 3 | B3 | Banana | Rod | - | + | - | + | K/K | Proteus sp. |

| 4 | B4 | Banana | Streptococci | + | - | - | + | K/K | Streptococcus sp. |

| 5 | Wm1 | Watermelon | Rod | + | + | - | + | K/A, H2S | Bacillus sp. |

| 6 | Wm2 | Watermelon | Rod | - | + | - | + | A/A | Enterobacter sp. |

| 7 | Wm3 | Watermelon | Cocci | + | + | - | + | K/K, H2S | Staphylococcus sp. |

| 8 | O1 | Orange | Cocci | + | + | - | - | K/A | Micrococcus sp. |

| 9 | O2 | Orange | Cocci | + | - weak | - | + | K/K | Streptococcus sp. |

| 10 | O3 | Orange | Cocci | + | + weak | - | + | K/K | Staphylococcus sp. |

| N/B: K/K: Alkaline slant/Alkaline butt i.e Red/Red–Non fermenter of glucose, lactose and sucrose; K/A: Alkaline slant/Acidic butt i.e Red/Yellow – Only glucose is fermented; A/A: Acidic slant/Acidic butt i.e Yellow/Yellow – Fermenter of glucose, lactose and sucrose + H2S B = H2S = Black | |||||||||

Pathogenicity of bacterial isolates on Musa acuminata (Banana) fruits

Results of pathogenicity of bacterial isolates on Musa acuminata (Banana) fruits are presented in Table 2. Banana fruits inoculated with Proteus sp. resulted in more tissue rot (2.33 cm) compared to Streptococcus sp. (0.90 cm). Differences in tissue rot among inoculated bacteria, and between inoculated bacteria and the control experiment were not significant (p ≤ 0.05).

| Table 2: Pathogenicity of bacterial isolates on Musa acuminata (Banana) fruits. | |

| Bacterial Isolates | Tissue Rot Diameter (cm) |

| Proteus sp. | 2.33 |

| Streptococcus sp. | 0.90 |

| Control | 0.00 |

| LSD | 1.10 |

Pathogenicity of bacterial isolates on Citrus sinensis (sweet orange) fruits

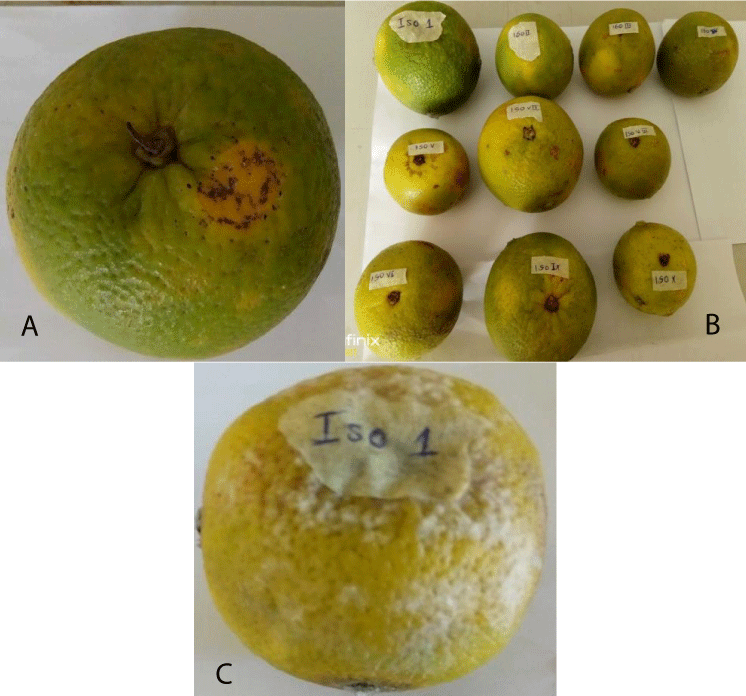

Results of pathogenicity of bacterial isolates on Citrus sinensis (Sweet orange) fruits are presented in Table 3. Of all the tested bacteria, only Micrococcus sp. yielded tissue rot in inoculated sweet orange fruits (Plate 1). Differences in tissue rot among inoculated bacteria, and between inoculated bacteria and the control experiment were not significant (p ≤ 0.05).

| Table 3: Pathogenicity of bacterial isolates onCitrus sinensis (Sweet orange) fruits. | |

| Bacterial Isolates | Tissue Rot Diameter (cm) |

| Micrococcus sp. | 0.55 |

| Streptococcus sp. | 0.00 |

| Staphylococcus sp. | 0.00 |

| Control | 0.00 |

| LSD (P ≤ 0.05)= NS | |

Plate 1: Rotted tissue on orange fruit inoculated with Micrococcus sp.

Pathogenicity of bacterial isolates on citrulluslanatus (watermelon) fruits

Different bacterial genera yielded different proportions of rot on inoculated watermelon fruits (Table 4). The highest tissue rot diameter of watermelon was induced by Enterobacter sp. (5.98 cm), followed by Bacillus sp. (5.13 cm) and lastly Staphylococcus sp. (4.88 cm). Differences in tissue rot among inoculated bacteria, and between inoculated bacteria and the control experiment were not significant (p ≤ 0.05).

| Table 4:Pathogenicity of bacterial isolates on Citrullus lanatus (Watermelon) fruits. | |

| Bacterial Isolates | Tissue Rot Diameter (cm) |

| Bacillus sp. | 5.13 |

| Enterobacter sp. | 5.98 |

| Staphylococcus sp. | 4.88 |

| Control | 0.00 |

| LSD (p ≤ 0.05) = 1.23 | |

Susceptibility of different fruits to tissue rot caused by bacterial pathogens

Results of the susceptibility of different fruits to tissue rot caused by bacterial pathogens are presented in Table 5. Watermelons were the most susceptible to rot (5.33 cm) by the tested bacterial pathogens, followed by Banana (0.94 cm), and lastly Sweet Orange (0.18 cm). Differences in the susceptibilities of different fruits to rot by bacterial pathogens were significant (p ≤ 0.05).

| Table 6: Fungi associated with rotted fruits in Lafia. | ||||

| S/No. | Isolate Code | Source | Isolate Identity | Division |

| 1 | ISO 1 | Orange | Alternaria sp. | Ascomycota |

| 2 | ISO 2 | Orange | Colletotrichum sp. | Ascomycota |

| 3 | ISO 3 | Orange | Curvularia geniculata | Ascomycota |

| 4 | ISO 4 | Banana | Aspergillusniger | Ascomycota |

| 5 | ISO 5 | Banana | Curvularia geniculata | Ascomycota |

| 6 | ISO 6 | Watermelon | Curvularia geniculata | Ascomycota |

| 7 | ISO 7 | Watermelon | Aspergillus sp. | Ascomycota |

| 8 | ISO 8 | Watermelon | Colletotrichum sp. | Ascomycota |

Fungi associated with rotted fruits in Lafia

Results of identification of fungi associated with rotted fruits in Lafia are presented in Table 6. All fungi isolated from the studied fruits belonged to the division Ascomycota. Oranges and Watermelon had the highest number of fungal isolates of 3 compared to banana which had 2. Fungi belonging to the genus Curvularia were the most isolated (37.50%), followed by both Aspergillusand Colletotrichum (25.00% respectively), and lastly Alternaria (12.500%).

| Table 5: Susceptibility of different fruits to tissue rot caused by bacterial pathogens. | |

| Fruits | Mean Diameter of Rotted Tissues (cm) |

| Banana | 0.94 |

| Sweet orange | 0.18 |

| Watermelon | 5.33 |

| LSD (p ≤ 0.05) = 1.43 | |

Pathogenicity of fungal isolates on Citrus sinensis (orange) fruits

Variations were observed in tissue rot of Citrus sinensis induced by different fungal pathogens (Table 7). The highest tissue rot diameter (2.40 cm) was induced by Alternaria sp. (Plate 2) followed by Curvularia geniculate (1.40 cm) and lastly Colletotrichum sp. (1.28 cm). Differences in tissue rot produced by the fungal isolates on inoculated orange fruits were significant (p ≤ 0.05).

| Table 7: Pathogenicity of fungal isolates on Citrus sinensis (Orange) fruits. | |

| Isolate | Tissue Rot Diameter (cm) |

| Alternaria sp. | 2.40 |

| Colletotrichum sp. | 1.28 |

| Curvularia geniculata | 1.40 |

| LSD (p ≤ 0.05)= 0.87 | |

Plate 2: (a) A Healthy orange fruit; (b) Inoculated orange fruits; (c) rotted orange fruit after 4 Days of inoculation with Alternaria sp.

Pathogenicity of fungal isolates on Musa acuminata (banana) fruits

The results of pathogenicity of fungal isolates on Musa acuminata fruits are presented in Table 8. The highest rot of banana fruit tissues was produced by A. niger (3.90 cm) (Plate 3), followed by Curvularia geniculate (3.40 cm). Differences in tissue rot induced by the tested fungal pathogens on banana fruits were not significant (p ≤ 0.05).

| Table 8: Pathogenicity of fungal isolates on Musa acuminata (banana) fruits | |

| Isolate | Tissue Rot Diameter (cm) |

| Aspergillus niger | 3.90 |

| Curvularia geniculata | 3.40 |

| LSD (p ≤ 0.05) = NS | |

Plate 3: (a) Healthy banana fruits; (b) Rotted banana fruits After 4 Days of inoculation with Apergillus niger.

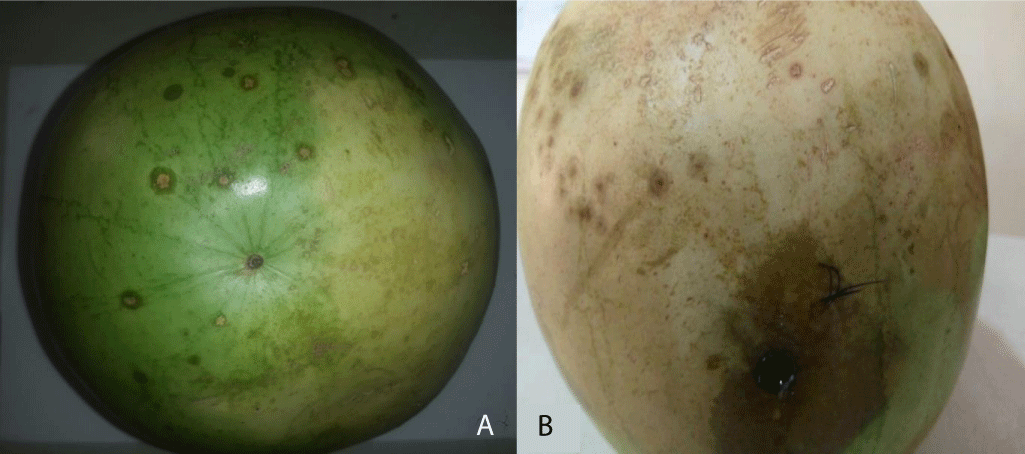

Pathogenicity of fungal isolates on Citrullus lannatus (watermelon) fruits

Results of pathogenicity of fungal isolates on Citrullus lannatus (Watermelon) fruits are presented in Table 9. Aspergillus sp. produced the highest tissue rot diameter on watermelon fruits (1.93 cm) (Plate 4), followed by Colletotrichum sp. (1.30 cm) and lastly Curvularia geniculate (1.20 cm). Differences in tissue rot diameters yielded by the tested fungi were not significant (p ≤ 0.05).

| Table 9: Pathogenicity of fungal isolates on Citrullus lannatus (Watermelon) fruits. | |

| Isolate | Tissue Rot Diameter (cm) |

| Curvularia geniculata | 1.20 |

| Aspergillus sp. | 1.93 |

| Colletotrichum sp. | 1.30 |

| LSD (p ≤ 0.05) = NS | |

Plate 4: (a) Healthy watermelon fruit; (b) Rotted watermelon fruit after 4 Days of inoculation with Aspergillus sp.

The Bacterium Enterobacter sp. was the major causative agent of post-harvest rot of watermelon and Enterobacteras was also reported as a major cause of rot in watermelons [38,39]. The excessively high moisture content of watermelons predisposes them to infection and colonization by fruit rot bacteria, resulting to significant tissue damage. Watermelons were also reported to contain rough succulent skins which allow adherence and proliferation of bacterial cells [40]. This probably accounts also for the highest occurrence of tissue rot in watermelons compared to other fruits in the study.

The highest rot of banana observed in the study was as a result of infection of banana fruits by bacteria from the genus Proteus. Similarly [41] reported brown rot in banana caused by Proteus sp. in Nigeria. The author also opined that the presence of high moisture, protein, carbohydrate and crude fiber in banana were major contributory factors to the high proliferation of Proteus sp. in banana tissues.

Orange fruits inoculated with fruit rot bacteria showed the least tissue rot compared to other evaluated fruits. The work of [42] also agreed that oranges are not easily degraded by fruit rot bacteria due to the presence of a resistant pericarp that prevents the proliferation of bacterial cells. The presence of citric acid in oranges also serves as a deterrent to the proliferation of tissue degrading microorganisms as reported by [43,44].

Fungi belonging to the genus Aspergillus, Alternaria, Colletotrichum and Curvularia were isolated from the studied fruits and were found to cause extensive rot when inoculated on healthy fruits. Post-harvest fruit rots of numerous crop plants have been reported by a number of workers. In related studies by [45], Alternaria alternata, and Colletotrichum musae were reported as the major pathogens while members of the Aspergillus genus were classified as secondary colonizers, hastening fruit rot of banana fruits in Andhra Pradesh, India. Other authors from India [46] also reported that Aspergillus sp., Curvuleria sp., Alternaria sp., and Colletotrichum sp. caused various degrees of rot and compromised citrus fruit quality in selected orchards of Sargodha, Pakistan. In Allahabad, India [47-49] also reported that Alternaria sp., Colletotrichum gloesporioides Aspergillus niger, and Curvularia sp., were among the major fungi responsible for post-harvest losses of guava andbanana fruit samples. Most recently, it has been reported that fruit rot of watermelon was caused by Aspergillus sp. in fruit stalls in Maiduguri, Nigeria [39].

Rot production by post-harvest fungal pathogens of fruit crops is majorly a result of the activity of tissue macerating enzymes synthesised by various fungal cells to achieve the breakdown of complex carbon compounds for the release of nutrients required for their metabolic activity. Enzyme synthetic ability and the activity of synthesised enzymes varies from one fungal genus to another. This accounts to a large extent for the variations in the extent of rot engineered by different post-harvest rot fungi.

The bacterial and fungal rots observed on fruits in the study are an indication of appreciable microbial contamination of fruit samples in the study area. There is need for improved handling of fruits after harvest to prevent losses due to bacterial rot in the study area.

The authors wish to appreciate the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFUND) Nigeria for financial support to carry out the field work.

- Gatto MA, Ippolito A, Linsalata V, Cascarano NA, Nigro F, Vanadia S, Di Venere D. Activity of extracts from wild edible herbs against postharvest fungal diseases of fruit and vegetables. Postharvest Biology and Technology.2011;61(1): 72-82.

- Negi PS. Plant extracts for the control of bacterial growth: efficacy, stability and safety issues for food application. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012 May 1;156(1):7-17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.03.006. Epub 2012 Mar 11. PMID: 22459761.

- Tripathi PN, Dubey K, Shukla AK. Use of some essential oils as post-harvest botanical fungicides in the management of grey mould of grapes caused by Botrytis cinerea. World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology. 2008; 24: 39-46. [ISSN: 0959-3993, Springer Netherlands]

- Fernandez-Cruz ML, Mansilla ML, Tadeo JL. Mycotoxins in fruits and their processed products: Analysis, occurrence and health implications. J Adv Res. 2010; 1: 113-122.

- Zain ME. Impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2011; 15: 129-144.

- Finlayson JE, Rimmer SR, Pritchard MK. Infection of Carrots by Sclerotinia sclerotiarum. Canadian Journal of Plant pathology. 1989; 11: 242.

- Swingle. https://www.worldcat.org/title/botany-of-citrus-and-its-wild-relatives-of-the-orange-subfamily-family-rutaceae-subfamily-aurantioideae/oclc/1613239.1943.

- Webber FC. Observations on the structure, life history and biology of Mycosphaerella ascophylli. Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 1967; 50: 583-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0007-1536(67)80090-1.

- Gmitter FG, Hu X. The possible role of Yunnan, China, in the origin of contemporary citrus species (rutaceae). Econ Bot .1990;44:267–277.

- Gorinstein S, Martı́n-Belloso Olga, Park YS, Haruenkit R, Lojek A, Ĉı́ž Milan , Trakhtenberg S. Comparison of some biochemical characteristics of different citrus fruits. Food Chemistry. 2001; 74(3): 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00157-1

- Wisniewski M, Wilson CL. Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruits and vegetables: recent advances. Hortscience. 1992; 27:94-98.

- Rippon JW, Conway TP, Domes AL. Pathogenic potential of Aspergillus and Penicillium species. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1965;27-32.

- El-Ghaouth A, Smilanick JL, Wilson CL. Enhancement of the performance of Candida saitoana by the addition of glycolchitosan for the control of postharvest decay of apple and citrus fruit. Postharvest biology and Technology. 2000; 19(1):103-110.

- Abirami LSS, Pushkala R, Srividya N. Antimicrobial activity of selected plant extracts against two important fungal pathogens isolated from Papaya fruit. International Journal of Research in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences. 2013; 4 (1): 234- 238.

- Konsue W, Dethoup T, Limtong S. Biological Control of Fruit Rot and Anthracnose of Postharvest Mango by Antagonistic Yeasts from Economic Crops Leaves. Microorganisms. 2020 Feb 25;8(3):317. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8030317. PMID: 32106522; PMCID: PMC7143844.

- Kubo I, Nakanishi K. Some terpenoid insect antifeedants from tropical plants. In: Advances in Pesticide Science (H. Geissbúhler, G.T.ed.) 1979.

- Dixit SN, Chandra H; Tiwari R, Dixit V. Development of a botanical fungicide against blue mould of mandarins. J. Stored Prod. Res. 1995; 31(2): 165-172

- Wilson M. Biocontrol of aerial plant diseases in agriculture and horticulture: current approaches and future prospects. J Ind Microbiol Biotech 1997;19: 188–191. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jim.2900436

- IITA. Improving scalable banana agronomy for small scale farmers in highland banana cropping systems in East Africa. https://www.iita.org/iita-project/improving-scalable-banana-agronomy/2016.

- FAO. Good Agricultural Practices for Bananas. https://www.fao.org/3/i6917e/i6917e.pdf 2016.

- Zeven AC, de Wet JMJ. Dictionary of cultivated plants and their regions of diversity excluding most ornamentals, forest trees and lower plants 1975.

- Zohary D, Hopf M. Domestication of Plant in the Old World. The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe and Nile Valley. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2000;316.

- Makaepea M,Beswa D, Afam IO Jideani. "Watermelon as a potential fruit snack." International Journal of food properties. 2019; 22(1): 355-370.

- Wehner, Todd C. "Watermelon." Vegetables. Springer, New York, NY. 2008; 381-418.

- Pal KK, Gardener M. Biological Control of Plant Pathogens. The Plant Health Instructor. 2006.

- Compant S, Duffy B, Nowak J, Clément C, Barka EA. Use of plant growth-promoting bacteria for biocontrol of plant diseases: principles, mechanisms of action, and future prospects. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005 Sep;71(9):4951-9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.4951-4959.2005. PMID: 16151072; PMCID: PMC1214602.

- Hajieghrari B, Torabi-Giglou M, Mohammadi MR, Davari M. Biological potantial of some Iranian Trichoderma isolates in the control of soil borne plant pathogenic fungi. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2008; 7(8): 967-972.

- Hermosa MR, Grondona I, Iturriaga EA, Diaz-Minguez JM, Castro C, Monte E, Garcia-Acha I. Molecular characterization and identification of biocontrol isolates of Trichoderma spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000 May;66(5):1890-8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.5.1890-1898.2000. PMID: 10788356; PMCID: PMC101429.

- Okigbo RN, Ikediugwu FEO. Studies on Biological Control of Postharvest Rot of Yam (Dioscorea spp.) with Trichoderma viride. Journal of Phytopathology. 2000; 148: 351-355.

- Kwon-Ndung EH, Akomolafe GF, Goler EE, Terna TP, Ittah MA, Umar ID, Waya JI, Markus M. Diversity Complex of Plant Species Spread in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation, 2016; 8(12): 334-350.

- Safrinet. Training manuals on Mycology. 2000.

- Samson RA, Visagie CM, Houbraken J, Hong SB, Hubka V, Klaassen CH, Perrone G, Seifert KA, Susca A, Tanney JB, Varga J, Kocsubé S, Szigeti G, Yaguchi T, Frisvad JC. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Stud Mycol. 2014 Jun;78:141-73. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.07.004. PMID: 25492982; PMCID: PMC4260807.

- International Committee on Food Microbiology and Hygiene, a committee of the International Union of Microbiological Societies (IUMS).

- Gibbons S. Anti-staphylococcal plant natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2004 Apr;21(2):263-77. doi: 10.1039/b212695h. Epub 2004 Mar 1. PMID: 15042149.

- Okigbo RN. Mycoflora of tuber surface of white yam (Dioscorea rotundata Poir) and postharvest control of pathogens with Bacillus subtilis. Mycopathologia. 2003;156(2):81-5. doi: 10.1023/a:1022976323102. PMID: 12733628.

- Terna TP, Okogbaa JI, Waya JI, Paul-Terna FC, Yusuf SO, Emmanuel NY, Simon A. Response of Different Mango and Tomato Varieties to Post-Harvest Fungal FruitRot in Lafia, Nassarawa State, Nigeria.IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology andFood Technology.2015; 9(12):106-109.

- Ojo O, Adebayo T, Wale O. Post-harvest control of botrydiplodia rot disease of watermelon using saprophytic isolates of yeast: International Journal of Agriculture and Crop Sciences. 2014; 7(12): 974-980.

- Sumby P, Barbian KD, Gardner DJ, Whitney AR, Welty DM, Long RD, Bailey JR, Parnell MJ, Hoe NP, Adams GG, Deleo FR, Musser JM. Extracellular deoxyribonuclease made by group A Streptococcus assists pathogenesis by enhancing evasion of the innate immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Feb 1;102(5):1679-84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406641102. Epub 2005 Jan 24. PMID: 15668390; PMCID: PMC547841.

- Jidda MB, Adamu MI. Rot Inducing Fungi of Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) Fruits in Storage and Fruit Stalls in Maiduguri, Nigeria. International Journal of Advanced Academic Research Sciences, Technology & Engineering. 2017.

- Dube J, Ddamulira G, Maphosa M. "Watermelon production in Africa: challenges and opportunities." International Journal of Vegetable Science. 2021; 27(3): 211-219.

- Oyewole OA, Al-Khalil S, Kalejaiye OA. The antimicrobial activities of ethanolic extracts of Basella alba on selected microorganisms. International Research Journal of Pharmacy www.irjponline.com.

- Sarkar S, Girisham S, Reddy SM. Incidence of post-harvest fungal diseases of banana fruit in Warangal market. Indian Phytopathology. 2009; 62(1): 103-105.

- Rajee O, Patterson J. Decolorization of Azo Dye (Orange MR) by an Autochthonous Bacterium, Micrococcus sp. DBS 2. Indian J Microbiol. 2011 Jun;51(2):159-63. doi: 10.1007/s12088-011-0127-0. Epub 2011 Jan 25. PMID: 22654158; PMCID: PMC3209883.

- Lotfy WA, Ghanem KM, El-Helow ER. Citric acid production by a novel Aspergillus niger isolate: II. Optimization of process parameters through statistical experimental designs. Bioresour Technol. 2007 Dec;98(18):3470-7. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.11.032. Epub 2007 Feb 20. PMID: 17317159.

- Mendonça LBP, Zambolim L, Badel JL. Bacterial citrus diseases: major threats and recent progress. J Bacteriol Mycol Open Access. 2017;5(4):340-350. DOI: 10.15406/jbmoa.2017.05.00143

- Srivastava R, LalA A. Incidence of Post-Harvest Fungal Pathogens in Guava and Banana in Allahabad. Journal of Horticultural Sciences,June 2009;85-89. https://jhs.iihr.res.in/index.php/jhs/article/view/565.

- Anitha M, Swathy SR, Venkateswari P. Prevalence of disease-causing microorganisms in decaying fruits with analysis of fungal and bacterial species. Int. J. Res. in Health Sciences. 2014;2(2): 547-54.

- Agarwal GP, Hasija SK. Alternaria rot of citrus fruits. Indian Phytopathology. 1967; 20:259-260.

- Chand JN, Rattan BK, Suryanarayana D.Epidemiology and control of fruit rot of citrus caused by Alternaria citri Ellis and Pierce. Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, India. Journal of Research. 1967; 4:217-222.