More Information

Submitted: April 26, 2022 | Approved: May 30, 2022 | Published: May 31, 2022

How to cite this article: Faruk MI, Rahman MME. Collection, isolation and characterization of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, an emerging fungal pathogen causing white mold disease. J Plant Sci Phytopathol. 2022; 6: 043-051.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jpsp.1001073

Copyright License: © 2022 Faruk MI, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum; White mold; Morphology; Sclerotia; Mycelia

Collection, isolation and characterization of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, an emerging fungal pathogen causing white mold disease

Md. Iqbal Faruk* and MME Rahman

Department of Plant Breeding, Takestan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Takestan, Iran

*Address for Correspondence: Md. Iqbal Faruk, Ph.D. Student, Plant Genetics and Breeding, Islamic Azad University, Qazvin, 4 wey padegan, Corner to Alley Shahid Babaei, services agriculture pardis(Green) Code postal: 3415665655, Takestan, Iran, Email: [email protected]

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary caused white mold disease with a wide distribution worldwide. For the control of the disease, it is fundamental to understand the identification, morphology, and genetic diversity of the fungus. The objective of this study was to collect and characterize S. sclerotiorum isolates from different regions of the country. The characteristics evaluated for the mycelium characterization were: the time required for the fungus to occupy the plate; density of the formed mycelium; coloration of the colonies and mycelia growth rate. Sclerotia assessments were based on the time for the formation of the first sclerotia total number formed per plate, the format of distribution in the plate, and the shape of the sclerotia formed by the isolates. Variability was observed for colony colour, type of growth, the diameter of mycelia growth, sclerotia initiation, and number and pattern of sclerotia formation among the isolates. The evaluated populations presented wide variability for the cultural and morphological characteristics, being predominant in the whitish colonies with fast-growing habitats. The majority of isolates produced a higher number of sclerotia near the margin of the plates and with diverse formats. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the isolates belonged to a similar group of publicly available S. sclerotiorum and were dissimilar from the group of S. minor, and S. trifolium and distinctly differ from S. nivalis group. The present study is the first evidence for morphological and genetic diversity study of S. sclerotiorum in Bangladesh. Therefore, this report contributes to more information about the morphological and genetic diversity of S. sclerotiorum and can be useful in implementing effective management strategies for the pathogen which caused white mold disease.

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary is commonly recognized as a facultative parasitic fungus, causing white mold disease in many crops. The fungus is one of the most important and devastating soil-inhabiting necrotrophic and non-host specific nearly cosmopolitan in its distribution with a broad host range [1]. The fungus infects more than 500 cultivated and wild plant species of angiosperms and gymnosperms [2,3] and causes substantial damage to its host under favorable environments. The pathogen produces sclerotia, which survive for long periods and attack the roots of growing and mature plants, resulting in root rot, basal stem canker, and wilt [4]. Sclerotinia Stem Rot (also known as white mold or Sclerotinia Stem and Root Rot) is one of the most important soil-borne diseases. Plant infection occurs either by myceliogenic germination of sclerotia or by ascospores released from apothecia during carpogenic germination of sclerotia. The myceliogenically germinating sclerotia are the main source of infection in processing crops leading to the rotting of aerial parts of the plant in contact with soil [5,6]. The disease can cause disastrous crop failure as disease incidences have been recorded from 60% - 80% and variable yield losses ranged from traces to 100% in several economically important crops worldwide [1,7]. Low temperatures, between 18-23 °C, and high humidity conditions, favor the occurrence of the pathogen. However, the use of contaminated and/or infected seeds, continuous crops in monoculture, a succession of crops with susceptible varieties, mild nocturnal temperatures (below 18 ºC), prolonged rains during cultivation, excessive nitrogen fertilization, and uncontrolled irrigation water supplied [8-10] cause white mold to spread, assuming great economic and social importance. Due to the abundant production of sclerotia, which allows for the survival of the fungus in the soil for more than 10 years, white mold is considered a disease difficult to control [11]. For sustainable management of diseases, it is essential to understand the etiology, epidemiological conditions, and aggressiveness of the pathogen isolates [12]. There is still relatively little information on the etiology, morphology, and genetic diversity of S. sclerotiorum in the literature, especially in Bangladesh. Morphological characteristics of S. sclerotiorum isolates collected from various hosts have already been reported in several studies in the country [13,14]. Dickson, [15] studied 33 isolates and found a difference between the density of mycelium and mycelia growth rates. Morral, et al. [16] studied 114 isolates of S. sclerotiorum collected from 23 hosts in Canada and found variations in colony color, mycelia growth rate, size, and shape of sclerotia. Corradini, [17] observed large variability in the growth and diameter of colonies, type, and color of mycelium, and production, weight, and distribution of sclerotia in 19 isolates from the Alto Paranaíba-MG region. Pariuad, et al. [18] evaluated the aggressiveness of the S. sclerotiorum isolates of different forms viz. by the infection efficiency, by the latent period, the spore production rate, and by the size of the lesion. Lehner, et al. [19] compared the aggressiveness of 20 S. sclerotiorum isolates and determined the relationship between aggressiveness and variability. Several molecular methods such as amplified fragment length polymorphism [20], random amplified fragment length polymorphism [21,22], microsatellite marker [23], sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) technique [24] and Universal Rice Primer Polymerase Chain Reaction (URP-PCR) [25] were used to determine the genetic diversity of fungus. Hence, there is a need to find out the diversity analysis of S. sclerotiorum infecting different host plants in Bangladesh for the development of sustainable management technologies. Therefore, the present study was conducted to ascertain the cultural, morphological, and molecular variability among different isolates of S. sclerotiorum obtained from infected several hosts in different regions of Bangladesh.

Collection, isolation, purification, and multiplication of S. sclerotiorum isolates

A minimum scale survey for white mold disease was conducted in the country during 2016-17 and 2017-18 cropping years. A total of one hundred and eighty isolates of S. sclerotiorum were excised from infected samples collected from 12 different districts. Symptoms of white mold disease on different crops were studied. Diseased plant samples and sclerotia were collected from different host plants in different regions of the country and stored under laboratory conditions in the Plant Pathology Division, Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute, Gazipur. The infected plant parts with some healthy portions were cut into small pieces followed by surface sterilized with sodium hypochlorite solution (0.2%) and was rinsed with sterilized distilled water 2-3 times. Then, the cut pieces were transferred in 9 cm Petri dishes containing 10-15 ml acid potato-dextrose agar (APDA). The Petri dishes will be incubated for 3-4 days in the dark at 25 ± 1 °C. On the other hand, the sclerotia were placed on a potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium after surface sterilized with sodium hypochlorite solution (0.2%) and incubated at 25 ± 1 °C for 3 days [26]. Each isolate was purified by transferring the single hyphal tip onto the fresh medium and preparing the pure culture of each isolate which was further multiplied.

Cultural and morphological variability

Mycelia disc of 5 mm diameter of each isolate was taken from actively growing colony of 4 days old culture and was transferred on to fresh PDA in Petri plate (90 mm diameter). All the cultures were incubated at 22 ± 1 °C in the incubator and observations of the cultural characters viz., the mycelial linear growth (mm) was recorded at 48 and 72 h while colony color and type of growth were recorded after 72 h after incubation. Four replications with three Petri plates per replication were used for each isolate. The morphological methods as suggested by Morrall, et al. [16] were used for the sclerotia formation i.e., initiation of sclerotia formation in days after incubation (DAI), number of sclerotia formation in plates, and pattern of sclerotia formation on PDA in Petri plates.

Molecular variability of S. sclerotiorum

The mycelium of each isolate was grown in potato dextrose broth by incubating at 22 ± 1 °C and 120 rpm. After 5–6 days, the mycelium of each isolate was filtered through Whatman filter no. 1, washed twice with the TE buffer, blot dried completely, and stored at − 70 °C till DNA isolation.

Total genomic DNA was extracted as described by Toda, et al. [27] from each isolate separately using the Wizard Genomic DNA extraction/ purification kit. The quantity and quality of DNA samples were tested by submerged horizontal agarose gel (0.8%) electrophoresis [28] along with a standard marker. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted with forwarding primer ITS4 (TCCTCCGCTTAT TGATATGC) and reverse primer ITS5 (GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG) [29] to amplify rDNA-ITS regions of the fungal isolate using commercial Master mix kit (Promega) following manufacturer’s instructions following programs for polymerase chain reaction (PCR): initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation of 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 62 °C for the 30s, polymerization at 68 °C for 1 min, and final elongation at 68 °C for 7 min. Five microliters of each amplification mixture were verified by agarose (1% w/v) gel electrophoresis in 0.5X Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer. The partial sequences were generated using the following ITS4 and ITS5 primers from a company (1st BASE Company, Malaysia).

Phylogenetic analysis

The PCR amplified products were purified using a commercial kit and then incubated at 37 °C for 60 min followed by 80 °C for 20 min. The nucleotide sequences were determined using dideoxy sequencing techniques at 1st BASE Company, Malaysia (taken as commercial service). Partial sequences were generated using the ITS4 and ITS5 primers. The ITS sequences were combined using the Bioedit software, checked manually, corrected, and then analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) available on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to search for nucleotide sequence homology in GenBank. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the using MEGA version 6.06 program [30,31] and a neighbor-joining tree was constructed using the Kimura two-parameter model. The phylogenetic tree was generated using the most identical fungal sequences available in the GenBank database. Confidence values were assessed from 1,000 bootstrap replicates of the original data.

Collection and cultural and morphological characteri-zation of isolates of S. sclerotiorum

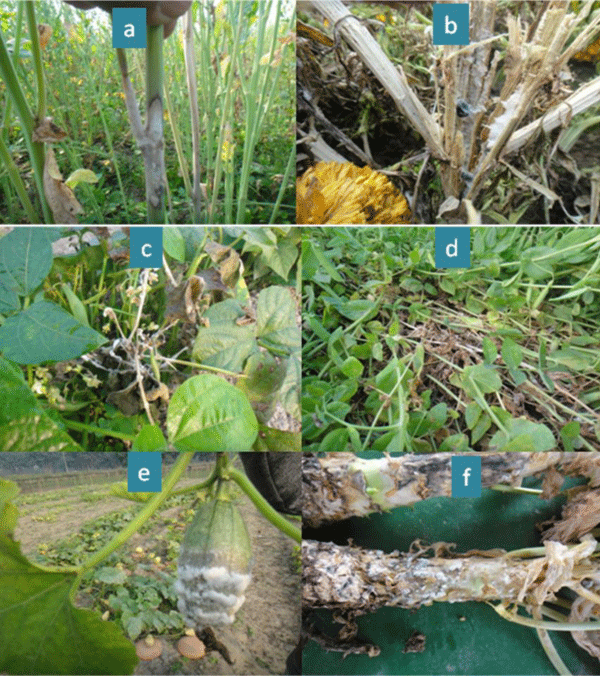

A total of one hundred and eighty isolates of S. sclerotiorum were excised from infected samples collected from different districts namely Rangpur, Dinajpur, Panchagarh, Lalmonirhat, Jessore, Sirajganj, Jamalpur, Mymensingh, Tangail, Pabna, Natore and Bogra of Bangladesh during 2016-17 and 2017-18 cropping years. The samples were collected from different host plants viz. mustard, marigold, bush bean, garden pea, broccoli, country bean, and ornamental gourd based on the symptom developed by the pathogen (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Common symptoms of white mold disease (a) mustard (b) marigold (c) bush bean (d) garden pea (e) ornamental gourd and (f) broccoli caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum; observing sclerotia inside marigold plant and infected plants of bush bean and broccoli.

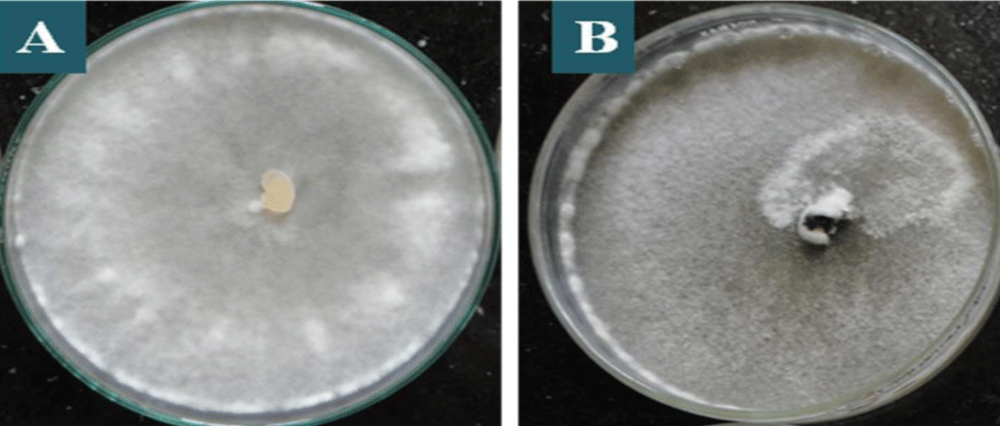

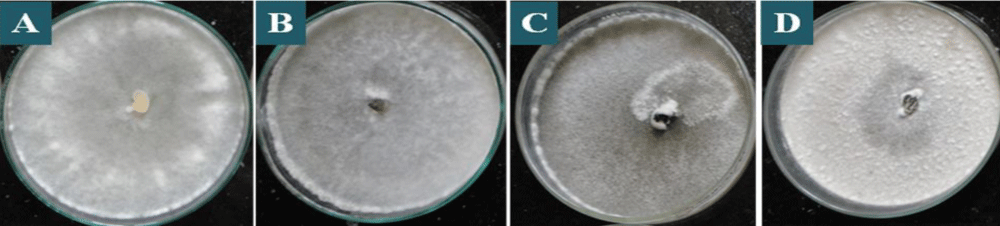

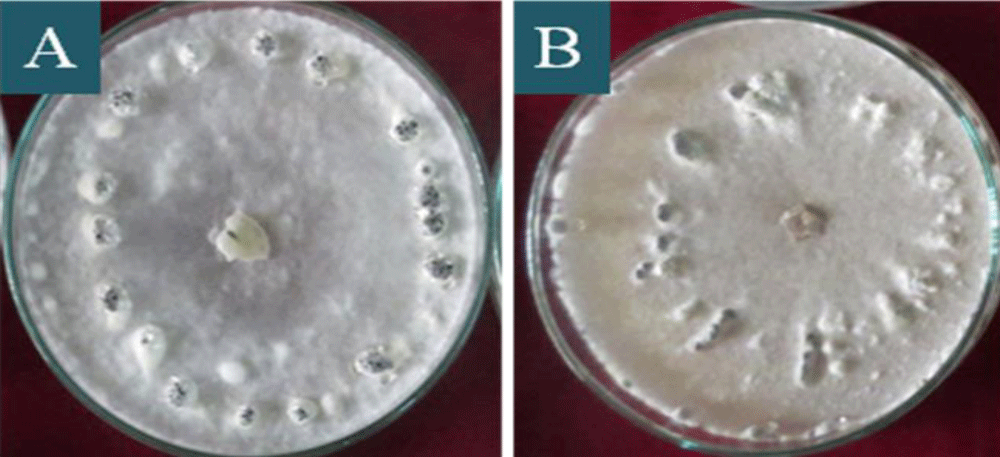

All the one hundred and eighty isolates of S. sclerotiorum were found to be variable to some extent in colony colour, and type of growth based on cultural characteristics of mycelium (Table 1). Few isolates showed dirty white colony colour, while the rest of the isolates showed whitish colony colour which is predominant among the isolates (Table 1 and Figure 2). Similar data were obtained by Grabicoski, [32] when evaluating 57 isolates of S. sclerotiorum and verified the predominance is white mycelium in S. sclerotiorum cultured in a BPD medium. Sharma, et al. [33] found differences in colony colour among the isolates collected from the different hosts as whitish and dirty white, however, white and grey white colony colour as observed by them were not found in any of the isolates in the present study. However, Ziman, et al. [34] observed a slight variation in colony colour of S. sclerotiorum isolates collected from different hosts, which differentiate from white to brown but the white colour was predominant in most of the isolates. The variations in the type of mycelia growth were also observed. The S. sclerotiorum isolates showed fluffy and sparse mycelia with the regular and irregular types of growth (Table 1 and Figure 3). Basha & Chatterjee, [35] also observed variation in the type of mycelial growth as colonies of seventeen isolates were fluffy, whereas three showed compact mycelia. Choudhary and Prasad, [36] also observed two types of mycelia growth as fluffy and compact among different isolates. However, Sharma, et al. [33] observed three types of scattered, smooth, and fluffy mycelia growth among different isolates.

Figure 2: Predominant staining in S. sclerotiorum colonies in PDA culture medium, after 7 days of incubation, being: A: whitish colony which is predominant among the isolates, B: dirty white colony.

Figure 3: Mycelial types in colonies of S. sclerotiorum on PDA culture medium, after 7 days of incubation, being: A: fluffy mycelia with regular, B: fluffy mycelia with irregular, C: sparse mycelia with regular, D: sparse mycelia with irregular type of growth.

| Table 1: Cultural variability of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolates collected from several host in different regions of Bangladesh. | |||

| Code of isolates | Cultural variability | ||

| Colony colour | Type of growth | Av. Mycelia growth at 72 hrs (cm) |

|

| SS1 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 7.50 |

| SS2 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 7.80 |

| SS3 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 5.60 |

| SS4 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 4.60 |

| SS5 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 5.30 |

| SS6 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.30 |

| SS7 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 5.70 |

| SS8 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 8.10 |

| SS9 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 8.00 |

| SS10 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 8.30 |

| SS11 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 6.40 |

| SS12 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 4.80 |

| SS13 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 3.90 |

| SS14 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 3.80 |

| SS15 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 4.60 |

| SS16 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 4.30 |

| SS17 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 3.80 |

| SS18 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 4.30 |

| SS19 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 4.10 |

| SS20 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 4.10 |

| SS21 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 6.10 |

| SS22 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 6.30 |

| SS23 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 4.65 |

| SS24 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 5.35 |

| SS25 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 8.00 |

| SS26 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 4.60 |

| SS27 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 7.60 |

| SS28 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 3.85 |

| SS29 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 5.72 |

| SS30 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 5.00 |

| SS31 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 8.00 |

| SS32 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 5.50 |

| SS33 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 5.30 |

| SS34 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 4.10 |

| SS35 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 6.27 |

| SS36 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.67 |

| SS37 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 7.25 |

| SS38 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 7.15 |

| SS39 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 4.16 |

| SS40 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 4.35 |

| SS41 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 4.72 |

| SS42 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 3.70 |

| SS43 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 3.65 |

| SS44 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 2.85 |

| SS45 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 7.05 |

| SS46 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.85 |

| SS47 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.63 |

| SS48 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.02 |

| SS49 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 6.85 |

| SS50 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 4.85 |

| SS51 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 8.15 |

| SS52 | Dirty white | Fluffy and irregular | 6.50 |

| SS53 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 5.62 |

| SS54 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 6.82 |

| SS55 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 5.45 |

| SS56 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.25 |

| SS57 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 5.15 |

| SS58 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.15 |

| SS59 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 5.25 |

| SS60 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 5.40 |

| SS61 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 4.15 |

| SS62 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.77 |

| SS63 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 5.15 |

| SS64 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 6.15 |

| SS65 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 7.15 |

| SS66 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 5.15 |

| SS67 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 2.65 |

| SS68 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 6.15 |

| SS69 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 5.12 |

| SS70 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 7.50 |

| SS71 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 7.15 |

| SS72 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 6.22 |

| SS73 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.17 |

| SS74 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 5.20 |

| SS75 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 4.25 |

| SS76 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 7.10 |

| SS77 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.10 |

| SS78 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 6.05 |

| SS79 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 5.18 |

| SS80 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 6.20 |

| SS81 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 6.12 |

| SS82 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 4.17 |

| SS83 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.25 |

| SS84 | Dirty white | Fluffy and irregular | 4.82 |

| SS85 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 3.95 |

| SS86 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.18 |

| SS86 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.18 |

| SS87 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 5.42 |

| SS88 | Dirty white | Fluffy and irregular | 5.40 |

| SS89 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.25 |

| SS90 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 6.36 |

| SS91 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 5.37 |

| SS92 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 5.15 |

| SS93 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 5.22 |

| SS94 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 5.10 |

| SS95 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 6.15 |

| SS96 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 6.20 |

| SS97 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.22 |

| SS98 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 4.53 |

| SS99 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 7.17 |

| SS100 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 7.47 |

| SS101 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 7.60 |

| SS102 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 7.75 |

| SS103 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 7.35 |

| SS104 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 5.72 |

| SS105 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 7.30 |

| SS106 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 6.97 |

| SS107 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 5.67 |

| SS108 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 6.85 |

| SS109 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 5.60 |

| SS110 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 7.47 |

| SS111 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 6.90 |

| SS112 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 4.95 |

| SS113 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 5.40 |

| SS114 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 6.27 |

| SS115 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 6.10 |

| SS116 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 4.07 |

| SS117 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.65 |

| SS118 | Dirty white | Fluffy and irregular | 4.15 |

| SS119 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 5.90 |

| SS120 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.75 |

| SS121 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 7.35 |

| SS122 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.40 |

| SS123 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 4.80 |

| SS124 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 7.15 |

| SS125 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 6.35 |

| SS126 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 4.85 |

| SS127 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 5.25 |

| SS128 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.20 |

| SS129 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 4.85 |

| SS130 | Dirty white | Fluffy and irregular | 6.25 |

| SS131 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 5.15 |

| SS132 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 3.95 |

| SS133 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 5.15 |

| SS134 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 5.18 |

| SS135 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 4.85 |

| SS136 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 2.95 |

| SS137 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.16 |

| SS138 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 4.85 |

| SS139 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 5.45 |

| SS140 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 4.16 |

| SS141 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 5.15 |

| SS142 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.85 |

| SS143 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 7.02 |

| SS144 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 7.72 |

| SS145 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 4.95 |

| SS146 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 4.85 |

| SS147 | Dirty white | Sparse and irregular | 6.15 |

| SS148 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 4.95 |

| SS149 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.25 |

| SS150 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.16 |

| SS151 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 7.10 |

| SS152 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 7.15 |

| SS153 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 4.93 |

| SS154 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 5.70 |

| SS155 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 6.85 |

| SS156 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 6.62 |

| SS157 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 7.50 |

| SS158 | Dirty white | Fluffy and irregular | 6.85 |

| SS159 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 5.72 |

| SS160 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 5.80 |

| SS161 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 4.85 |

| SS162 | Dirty white | Sparse and regular | 5.15 |

| SS163 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 4.10 |

| SS164 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 4.18 |

| SS165 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.26 |

| SS166 | Whitish | Fluffy and regular | 4.80 |

| SS167 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 4.95 |

| SS168 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 6.12 |

| SS169 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 5.00 |

| SS170 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 4.67 |

| SS171 | Whitish | Fluffy and irregular | 3.80 |

| SS172 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.35 |

| SS173 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 3.40 |

| SS174 | Whitish | Sparse and regular | 6.42 |

| SS175 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 4.85 |

| SS176 | Whitis | Sparse and regular | 6.65 |

| SS177 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 6.90 |

| SS178 | Dirty white | Fluffy and regular | 2.85 |

| SS179 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 7.35 |

| SS180 | Whitish | Sparse and irregular | 7.80 |

The mycelia growth rate of S. sclerotiorum differed considerably among the isolates (Table 1). The average mycelial growth ranges from 2.65 cm to 8.10 cm at 72 hrs after inoculation was recorded. According to the mycelia growth at 72 hrs after inoculation, all the isolates were divided into three groups’ viz. slow-growing isolates (average mycelial growth as colony diameter 0.0-4.0 cm at 72 hrs after inoculation), intermediated growing isolates (average mycelial growth as colony diameter 4.10-6.99 cm at72 hrs after inoculation) and fast-growing isolates (average mycelial growth as colony diameter ≥7.00 cm at72 hrs after inoculation). In the present study, the S. sclerotiorum isolates SS67, SS44, SS178, SS136, SS171, SS43, SS42, SS14, SS17, SS171, SS28, SS13, SS85 and SS132 isolates showed slow mycelia growth as colony diameter was 2.65, 2.85, 2.85, 2.95, 3.40, 3.65, 3.70, 3.80, 3.80, 3.80, 3.85, 3.90, 3.95 and 3.95 cm after 72 hrs of incubation, respectively, while the isolates SS143, SS45, SS76, SS 151, SS38, SS65, SS71, SS124, SS152, SS99, SS37, SS105, SS103, SS121, SS179, SS100, SS110, SS1, SS 70, SS157, SS27, SS101, SS144, SS102, SS2, SS180, SS9, SS25, SS31, SS8, SS51, SS10 and SS36 showed fast mycelia growth with colony diameter of 7.02, 7.05, 7.10, 7.10, 7.15, 7.15, 7.15, 7.15, 7.15, 7.17, 7.25, 7.30, 7.35, 7.35, 7.35, 7.47, 7.47, 7.50, 7.50, 7.50, 7.60, 7.60, 7.72, 7.75, 7.80, 7.80, 8.00, 8.00, 8.00, 8.10, 8.15 8.30 and 8.67 cm after 72 hrs of incubation, respectively (Table 1). The rest of the collected isolates of S. sclerotiorum showed intermediate mycelia growth with colony diameter from 4.01 to 6.99 cm after 72 hrs of incubation. However, all intermediated and fast-growing isolates of S. sclerotiorum covered full mycelia growth in the 90 mm diameter Petri plates within 96 h of incubation while the slow-growing isolates of S. sclerotiorum covered full mycelia growth in the 90 mm diameter Petri plates after 120 h of incubation. A similar trend was also reported by Corradini, [17] who evaluated 19 isolates of S. sclerotiorum and observed that the colonies reached the maximum diameter of the plaque at the end of 120 hrs of incubations. Garg, et al. [37] reported significant differences between isolates with the colony diameter measured after 24 and 48 h of incubation. Ahmadi, et al. [38] examined seven populations of S. sclerotiorum associated with stem rot of important crops and weeds and based on mycelia growth; these seven populations were classified into four groups i.e. very fast, fast, intermediate and slow-growing.

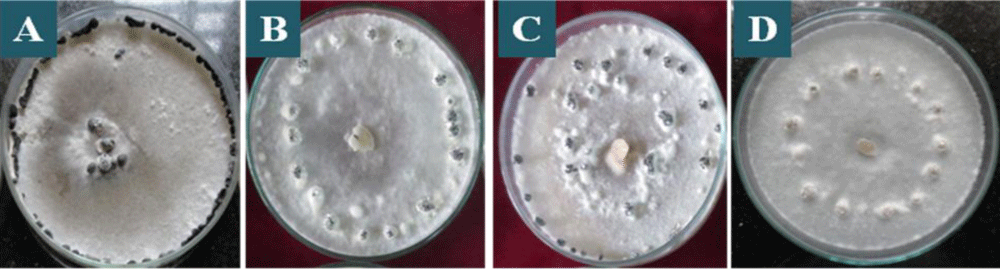

All the isolates presented sclerotia production (Table 2). The size, shape, and number, pattern of sclerotia formation varied among the isolates (Figure 4 and Table 2). Four different patterns of sclerotia formation viz. near to rim of the plaque, attached to the rim of the plaque, scattered all around the plaque and ring centre of the plaque, were observed among the isolates were near to the rim is predominant (Figure 4 and Table 2). Similar data were found by Zanatta, et al. [39] who reported that the distribution of sclerotia was 60% near the margin of the plaque, 25% scattered in the plaque, and 15% concentric circle in the plaque. As the shape of the sclerodes formed, 34.44% of the isolates presented a rounded shape and 65.56% irregular shape. These data corroborate those of Grabicoski, [32] who classified most of the isolates (65%) produced as diverse, with varied formats of sclerodes.

Figure 4: Distribution of sclerotia on the plaques of S. sclerotiorum colonies in PDA culture medium, after 20 days of incubation, being: A: attached to rim of the plaque, B: near to rim of the plaque, C: scattered all around of the plaque, D: ring centre of the plaque.

| Table 2: Morphological variability of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolates collected from several host in different regions of Bangladesh. | |||

| Sclerotia formation | |||

| Code of isolates | Initiation (DAI) | Average number sclerotia plate-1 | Pattern of sclerotia production |

| SS1 | 5 | 53.50 | Attached to rim |

| SS2 | 5 | 52.00 | Near to rim |

| SS3 | 7 | 36.50 | Near to rim |

| SS4 | 8 | 22.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS5 | 8 | 24.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS6 | 6 | 50.00 | Near to rim |

| SS7 | 8 | 31.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS8 | 6 | 56.50 | Near to rim |

| SS9 | 7 | 47.50 | Attached to rim |

| SS10 | 5 | 47.50 | Near to rim |

| SS11 | 8 | 22.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS12 | 9 | 24.50 | Near to rim |

| SS13 | 8 | 20.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS14 | 13 | 11.50 | Near to rim |

| SS15 | 8 | 23.50 | Near to rim |

| SS16 | 8 | 20.50 | Near to rim |

| SS17 | 12 | 20.50 | Scattered all around |

| SS18 | 11 | 21.50 | Near to rim |

| SS19 | 12 | 18.50 | Near to rim |

| SS20 | 7 | 28.00 | Near to rim |

| SS21 | 7 | 31.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS22 | 6 | 43.50 | Attached to rim |

| SS23 | 10 | 20.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS24 | 9 | 28.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS25 | 8 | 25.50 | Near to rim |

| SS25 | 9 | 25.50 | Near to rim |

| SS26 | 13 | 15.00 | Near to rim |

| SS27 | 9 | 42.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS28 | 5 | 56.50 | Near to rim |

| SS29 | 6 | 41.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS30 | 9 | 35.00 | Near to rim |

| SS31 | 5 | 52.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS32 | 12 | 19.00 | Near to rim |

| SS33 | 9 | 40.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS34 | 8 | 42.50 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS35 | 5 | 56.00 | Near to rim |

| SS36 | 10 | 35.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS37 | 13 | 18.50 | Near to rim |

| SS38 | 8 | 42.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS39 | 12 | 19.00 | Near to rim |

| SS40 | 10 | 27.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS41 | 13 | 15.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS42 | 9 | 32.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS43 | 8 | 10.00 | Near to rim |

| SS44 | 8 | 10.00 | Near to rim |

| SS45 | 10 | 25.00 | Near to rim |

| SS46 | 8 | 35.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS47 | 9 | 28.00 | Near to rim |

| SS48 | 6 | 43.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS49 | 7 | 35.50 | Near to rim |

| SS50 | 11 | 17.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS51 | 12 | 34.50 | Near to rim |

| SS52 | 11 | 23.50 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS53 | 10 | 30.00 | Near to rim |

| SS54 | 6 | 53.50 | Scattered all around |

| SS55 | 7 | 40.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS56 | 11 | 30.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS57 | 13 | 19.50 | Near to rim |

| SS58 | 11 | 36.00 | Near to rim |

| SS59 | 10 | 30.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS60 | 8 | 37.50 | Attached to rim |

| SS61 | 12 | 25.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS62 | 13 | 23.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS63 | 10 | 26.00 | Near to rim |

| SS64 | 11 | 27.00 | Near to rim |

| SS65 | 7 | 41.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS66 | 12 | 35.00 | Near to rim |

| SS67 | 13 | 18.50 | Scattered all around |

| SS68 | 8 | 32.50 | Near to rim |

| SS69 | 11 | 28.50 | Scattered all around |

| SS70 | 5 | 60.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS71 | 7 | 43.00 | Near to rim |

| SS72 | 12 | 29.50 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS73 | 13 | 20.50 | Scattered all around |

| SS74 | 13 | 22.50 | Scattered all around |

| SS75 | 12 | 21.00 | Near to rim |

| SS76 | 7 | 42.50 | Near to rim |

| SS77 | 12 | 18.00 | Near to rim |

| SS78 | 11 | 25.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS79 | 10 | 30.50 | Attached to rim |

| SS80 | 7 | 45.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS81 | 5 | 51.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS82 | 8 | 24.00 | Near to rim |

| SS83 | 6 | 47.50 | Near to rim |

| SS84 | 5 | 40.00 | Near to rim |

| SS85 | 13 | 24.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS86 | 12 | 33.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS86 | 12 | 27.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS87 | 7 | 46.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS88 | 10 | 28.00 | Near to rim |

| SS89 | 10 | 32.50 | Near to rim |

| SS90 | 6 | 51.00 | Near to rim |

| SS91 | 9 | 35.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS92 | 8 | 31.00 | Near to rim |

| SS93 | 12 | 25.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS94 | 13 | 21.00 | Near to rim |

| SS95 | 12 | 32.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS96 | 9 | 30.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS97 | 6 | 58.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS98 | 7 | 34.50 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS99 | 7 | 48.00 | Near to rim |

| SS100 | 5 | 64.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS101 | 8 | 35.00 | Near to rim |

| SS102 | 5 | 59.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS103 | 8 | 40.00 | Near to rim |

| SS104 | 11 | 33.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS105 | 8 | 41.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS106 | 5 | 57.50 | Near to rim |

| SS107 | 7 | 58.50 | Attached to rim |

| SS108 | 9 | 38.50 | Near to rim |

| SS109 | 7 | 49.50 | Near to rim |

| SS110 | 8 | 42.50 | Scattered all around |

| SS111 | 9 | 35.00 | Near to rim |

| SS112 | 9 | 43.50 | Scattered all around |

| SS113 | 8 | 41.50 | Near to rim |

| SS114 | 7 | 44.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS115 | 6 | 56.00 | Near to rim |

| SS116 | 7 | 51.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS117 | 13 | 21.50 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS118 | 13 | 14.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS119 | 11 | 22.50 | Attached to rim |

| SS120 | 12 | 20.00 | Near to rim |

| SS121 | 13 | 18.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS122 | 11 | 29.50 | Near to rim |

| SS123 | 12 | 20.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS124 | 9 | 35.50 | Near to rim |

| SS125 | 6 | 55.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS126 | 10 | 28.50 | Near to rim |

| SS127 | 9 | 29.50 | Scattered all around |

| SS128 | 12 | 20.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS129 | 8 | 29.00 | Near to rim |

| SS130 | 6 | 42.50 | Attached to rim |

| SS131 | 13 | 24.00 | Near to rim |

| SS132 | 13 | 18.00 | Near to rim |

| SS133 | 12 | 26.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS134 | 11 | 17.50 | Near to rim |

| SS135 | 7 | 30.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS136 | 15 | 9.00 | Near to rim |

| SS137 | 14 | 34.00 | Near to rim |

| SS138 | 15 | 16.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS139 | 12 | 28.50 | Near to rim |

| SS140 | 15 | 16.00 | Near to rim |

| SS141 | 14 | 30.00 | Near to rim |

| SS142 | 8 | 38.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS143 | 7 | 45.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS144 | 15 | 17.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS145 | 14 | 17.50 | Attached to rim |

| SS146 | 15 | 22.50 | Near to rim |

| SS147 | 11 | 35.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS148 | 12 | 29.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS149 | 9 | 30.00 | Near to rim |

| SS150 | 14 | 16.50 | Scattered all around |

| SS151 | 6 | 52.00 | Near to rim |

| SS152 | 14 | 19.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS153 | 8 | 40.00 | Near to rim |

| SS154 | 7 | 42.50 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS155 | 7 | 56.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS156 | 13 | 35.00 | Near to rim |

| SS157 | 14 | 18.50 | Near to rim |

| SS158 | 6 | 42.00 | Near to rim |

| SS159 | 14 | 19.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS160 | 12 | 27.00 | Near to rim |

| SS161 | 12 | 27.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS162 | 13 | 15.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS163 | 14 | 32.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS164 | 15 | 10.00 | Near to rim |

| SS165 | 15 | 10.00 | Near to rim |

| SS166 | 14 | 25.00 | Near to rim |

| SS167 | 8 | 35.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS168 | 12 | 28.00 | Near to rim |

| SS169 | 8 | 43.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS170 | 9 | 35.50 | Near to rim |

| SS171 | 13 | 17.00 | Scattered all around |

| SS172 | 8 | 34.50 | Near to rim |

| SS173 | 12 | 23.50 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS174 | 13 | 30.00 | Double ring near to rim and centre |

| SS175 | 6 | 53.50 | Attached to rim |

| SS176 | 8 | 40.00 | Attached to rim |

| SS177 | 12 | 30.00 | Near to rim |

| SS178 | 14 | 19.50 | Near to rim |

| SS179 | 12 | 36.00 | Near to rim |

| SS180 | 12 | 30.00 | Near to rim |

Regarding the time required for the formation of the first sclerotia of each isolate, there was a distinct difference among the isolates. The time for sclerotia formation varied from 5.00 days to 15.00 days. Similar data were found by Grabicoski, [32], and the meantime for sclerotia formation ranged from 11.8 to 15.4 days. For Abreu, [40], the time for the formation of sclerodium in the isolates evaluated ranged from 4.00 to 12.44 days. Zanatta, et al. [39] and reported that the time for sclerotia formation varied from 10.67 to 18.0 days.

The number of sclerotia per plaque of different isolates varied considerably and the range from 9.00 to 64.00 sclerotia was produced per plaque (Table 2). The S. sclerotiorum isolates SS136, SS43, SS44, SS14, SS118, SS26, SS 41, SS138, SS140, SS 150, SS 50, SS144, SS170, SS134 , SS145, SS77, SS121, SS132, SS157, SS19, SS 37, SS67, SS32, SS39, SS152, SS159, SS57, SS177, SS23, SS120, SS123 and SS128 were showed lower average number of sclerotia production per plaque range from 9.00 to 20.00 sclerotia per plaque, where isolates SS80, SS143, SS87, SS9, SS10, SS83, SS99, SS109, SS6, SS81, SS90, SS116, SS2, SS31, SS151, SS1, SS54, SS175, SS125, SS35, SS115, SS155, SS8, SS28, SS106, SS97, SS107, SS102, SS70 and SS100 showed higher average number of Sclerotia per plate range from 45.00 to 64.00 sclerotia per plaque (Table 2). The data found in the present study corroborating with studies developed by Abreu, [40], and the number of sclerodes ranged from 10.33 to 46.00, and by Grabicoski, [32], ranging from 16.6 to 57.2 sclerotia per plaque. Ghasolia and Shivpuri, [41] also observed variability among 38 isolates of S. sclerotiorum, which showed variation in their morphological traits like a sclerotial number, size, position, and pattern. Kumar, et al. [26] also examined sufficient diversity in size of sclerotia and pattern of sclerotia among isolates S. sclerotiorum. As to the shape of the sclerotia formed, only 37.78% of isolates presented a rounded shape (68 isolates) and the rest of the isolates (63.22%) presented sclerotia with a different format (112 isolates) (Figure 5). These data corroborated those of Grabicoski, [32] who classified most of the isolates (65%) as diverse, with varied formats. Zanatta, et al. [39] reported three different shapes of sclerotia formed in S. sclerotiorum, 25% rounded shape, 30% irregular shape, and 45% in a different format.

Figure 5: Format of the sclerotia formed on the plaques of S. sclerotiorum colonies in PDA culture medium, after 20 days of incubation, being: A: rounded shaped, B: divers format.

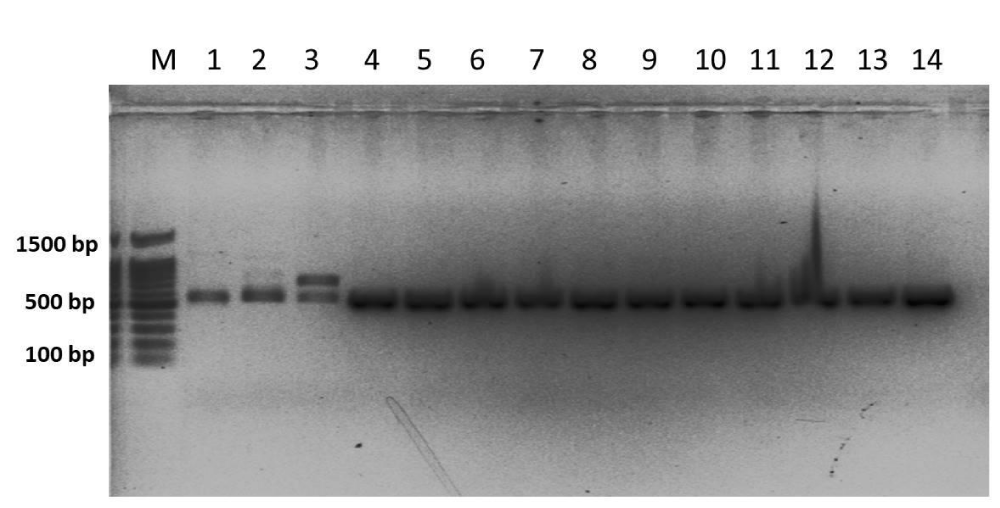

Molecular characterization and genetic diversity of S. sclerotiorum

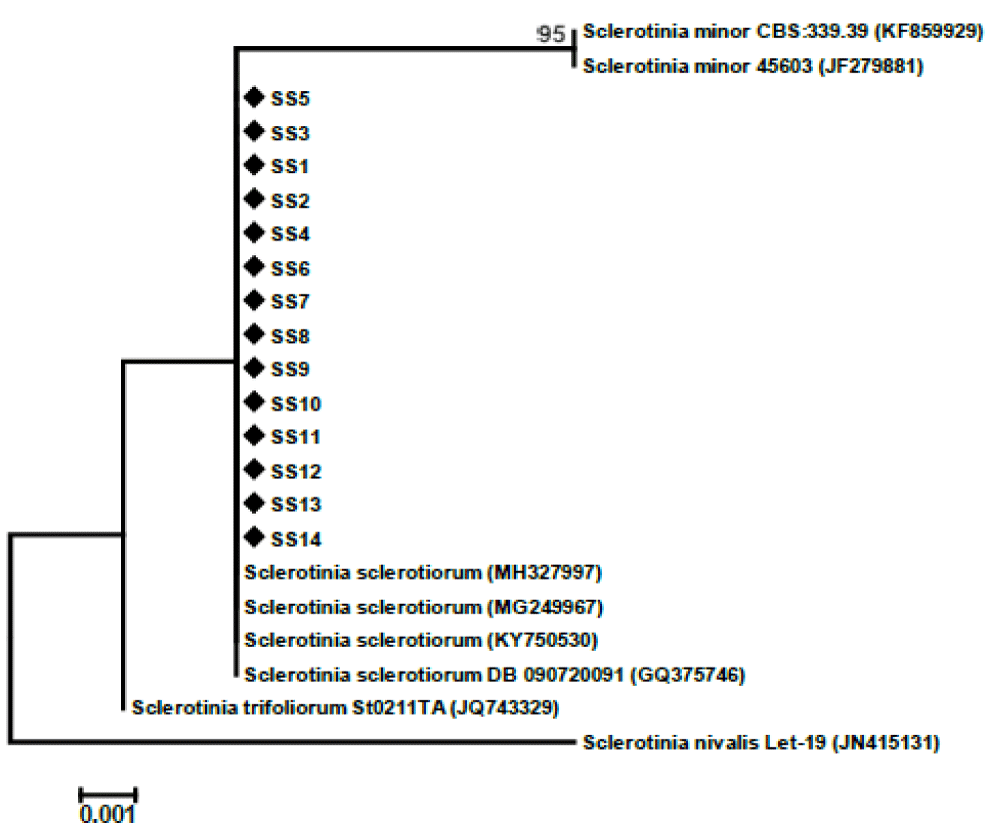

A total of 14 samples were selected for DAN extraction (Figure 6). After DNA extraction, the DNA was used for PCR using ITS primers ITS4 (TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) and ITS5 (GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG) for amplification ITS regions. During PCR all the DNA samples of the isolates were amplified properly and those were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure 7). Amplified DNA was sent for sequencing for molecular characterization. Molecular characterization of the 14 isolates by ITS sequencing indicated all the tested isolates were identified as Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. The ITS sequences of the 14 isolates were identical to many publicly available S. sclerotiorum sequences (eg. KY750530). Phylogenetic analysis of the isolates based on ITS sequences revealed the isolates belonged to a similar group of publicly available S. sclerotiorum and were dissimilar from the group of S. minor, S. trifolium, and distinctly different from the S. nivalis group (Figure 4).

Figure 6: DNA amplification profile of fourteen S. sclerotiorum isolates with ITS4 forward and ITS5 reverse primer. M-50 bp ladder.

Figure 7: Phylogenetic tree based on internal transcribed spacer sequences revealing the phylogenetic relationships among the Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolates and related species. The 14 isolates from this study are indicated in the tree with a black diamond.

The evaluated populations presented wide variability for the cultural and morphological characteristics, being predominant in the whitish colonies. The majority of isolates produced a higher number of sclerotia near the margin of the plates and with diverse formats. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the isolates belonged to a similar group of publicly available S. sclerotiorum and were dissimilar from the group of S. minor, and S. trifolium and distinctly differ from S. nivalis group. The present study is the first evidence for morphological and genetic diversity study of S. sclerotiorum in Bangladesh. Therefore, this report contributes to more information about the epidemiology of the disease and can be useful in implementing effective management strategies for the disease.

The authors thankfully acknowledged Project Implementation Unit-BARC, NATP-2 Bangladesh Agricultural Research Council, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215 to provide financial support for the pieces of research under the CRG-599 subproject. The authors also acknowledged to Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute, Gazipur to provide logistic support for this research work. Thanks go to Mr. Md. Abdur Razzak and Mr. Zamil Akter (Scientific Assistant) for their assistance in completing the research in the field.

- Mehta N. Sclerotinia stem rot-an emerging threat in mustard. Plant Dis Res. 2009;24: 72–73.

- Saharan GS, Mehta N. Sclerotinia Diseases of Crop Plants: Biology, Ecology and Desease Management. India: Springer. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8408-9

- Sharma P, Meena PD, Verma PR, Saharan GS, Mehta N, Singh D, Kumar A. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib) de Bary causing sclerotinia rot in Brassicas: a review. J Oilseed Brassica 2015;6:1–44.

- Duncan RW, Dilantha Fernandoa WG, Rashidb KY. Time and burial depth influencing the viability and bacterial colonization of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Soil Biol Bioche. 2006;38: 275-284.

- Gao X, Han Q, Chen Y, Qin H, Huang L. Biological control of oilseed rape Sclerotinia stem rot by Bacillus subtilis strain Em7. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 2014; 24: 39-52.

- Purdy LH. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: History, diseases, symptomatology, host range, geographic distribution, and impact. Phytopathology. 1979; 69: 875-880.

- Shukla AN. Estimation of yield losses to Indian mustard Brassica juncea due to Sclerotinia stem rot. J Phytol Res. 2005;18:267-268.

- Leite RM VBC. Occurrence of diseases caused by Scleriotinia sclerotiorum in sunflower and soybean(p. 3). Londrina: Embrapa soybean, Technical Communiqué.2005.

- Juliatti FC, Juliatti FC. White stem rot of soybean: Management and use of fungicides in search of sustainability in production systems (p. 33). Uberlândia: Composer. 2010.

- Silva LHCP, Campos HD, Silva JRC. Management of soybean white mold. In LHCP Silva, HD Campos, JRC Silva (Eds.), Phytosanitary management of agroenergy crops. 2010; 205-214.

- Reis EM, Tomazini SL. Viability of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum sclerotia at two depths in soil. Summa Phytopathologica.2005;31: 97-99.

- Kohli DK, Bachhawat AK. CLOURE: Clustal Output Reformatter, a program for reformatting ClustalX/ClustalW outputs for SNP analysis and molecular systematics. Nucleic Acids Res.2003;31(13): 3501-3502. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg502

- Rahman MME, Dey TK, Hossain DM, Nonaka M, Harada N (2015). First report of white mold caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum on jackfruit. Australasian Plant Dis Notes 1010 DOI 10.1007/s13314-014-0155-9.

- Rahman MME, Suzuki K, Islam MM. et al. Molecular characterization, mycelial compatibility grouping, and aggressiveness of a newly emerging phytopathogen, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, causing white mold disease in new host crops in Bangladesh. J Plant Pathol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42161-020-00503-8

- Dickson. Studies on Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (LIB) de Barry. 1930; 91. Cornell Univ, Ithaca-NY.

- Morral RAA, Duczek L, Sheard JW. Variations and correlations within morphology, pathogenicity, and pectolytic enzyme activity in Sclerotinia from Saskatchewan. Canadian J Botany.1972;50(10): 767-85. https://doi.org/10.1139/b72-095

- Corradini HT. Characterization in pure culture and pathogenicity of Barry’s (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum) (Lib.) Isolates, associated with soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) in the Alto Paranaíba-MG region (Dissertation, Master’S Degree, School of Agriculture of Lavras, Lavras, Brazil). 1989.

- Pariuad B, Ravigné V, Halkett F, Goyeau H, Carlier J, Lannou C. Aggressiveness anda its role in the adaptation of plant pathogens. Plant Pathol.2009; 58: 409-424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.2009.02039.x

- Lehner MS, Paula Junior TJ, Hora Junior BT, Teixeira H, Vieira RF, Carneiro JES, Mizubuti ESG. Low genetic variability in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum populations from common bean fields in Minas Gerais State, Brazil, at regional, local and micro scales. Plant Pathol.2015;64: 921-931. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12322

- Cubeta MA, Cody BR, Kohli Y, Kohn LM. Clonality in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum on infected cabbage in eastern North Carolina. Phytopathology. 1997;87:1000–1004.

- Yli-Mattila T, Hannukkala A, Paavanen-Huhtala S, Hakala K. Prevalence, species composition, genetic variation and pathogenicity of clover rot (Sclerotinia trifolioum) and Fusarium spp. in red colver in Finland. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2010;126:13–27.

- Thilagavathi R, Nakkeeran S, Raguchander T, Samiyappan R. Morphological and genomic variability among Sclerotium rolfsii populations. Bioscan. 2013;8(4):1425–1430.

- Meinhardt LW, Wulf NA, Bellato CM, Tsai SM. Telomere and microsatellite primers reveal diversity among Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolates from Brazil. Fitopatol Bras.2002;27:211–215.

- Li CX, Liu SY, Sivasithamparam K, Barbetti MJ. New sources of resistance to Sclerotinia stem rot caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorumin Chinese and Australian Brassica napus and B. juncea germplasm screened under Western Australian conditions. Australas. Plant Pathol.2009;38(2):149–152.

- Aggarwal R, Sharma V, Kharbikar LL, Renu. Molecular characterization of Chaetomium species using URP-PCR. Genet. Mol Biol. 2008;31(4):943–946.

- Kumar P, Rathi AS, Singh JK, Berwal MK, Kumar M, Kumar A, Singh D. Cultural, morphological and Pathogenic diver-sity analysis of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum causing Sclerotinia rot Indian mustard. Indian J Ecol. 2016;43(1):463–472.

- Toda T, Hyakumachi M, Suga H, Kageyama K, Tanaka A, Tani T. Differentiation of Rhizoctonia AG-D isolates from turfgrass into subgroups I and II based on rDNA and RAPD analysis. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1999;105:835-846.

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Miniatis T. Molecular cloning a laboratory manual, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York. 1989; pp 856–965.

- White TJ, Bruns TD, Lee SB, Taylor JW. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, eds. by Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ. 1990;pp. 315-322. Academic Press, New York, USA.

- Hossain MM, Sultana F, Miyazawa M, Hyakumachi M. Plant growth-promoting fungus Penicillium spp. GP 15-1 enhances growth and confers protection against damping-off and anthracnose in the cucumber. J Oleo Sci. 2014;63:391-400.

- Islam S, Akanda AM, Prova A, Islam MT, Hossain MM. Isolation and identification of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from cucumber rhizosphere and their effect on plant growth promotion and disease suppression. Front. Microbiol. 2016;6:1360.

- Grabicoski EMG. Morphological and pathogenic characterization of isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) From Bary and detection in soybean seeds (Dissertation, Masters in Agronomy, Area of Concentration-Phytopathology, State University of Ponta Grossa, Ponta Grossa). 2012.

- Sharma P, Meena PD, Kumar S, Chauhan JS. Genetic diversity and morphological variability of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolates of oilseed Brassica in India. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2013;7:1827-1833.

- Ziman L, Jedryezka M, Srobarova A. Relationship between morphological and biochemical characterstics of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolates and their aggressivity. Z Pfa Krank Pfa Schutz. 1998;105:283–288.

- Basha SA, Chatterjee SC. Variation in cultural, mycelial compatibility and virulence among the isolate of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Indian Phytopathol. 2007;60:167–172

- Choudhary V, Prasad L. Morphopathological, genetic variations and population structure of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Int J Plant Res. 2012;25:178–183.

- Garg H, Kohn LM, Andrew M, Li H, Sivasithamparam K, Barbetti MJ. Pathogenicity of morphologically different isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum with Brassica napus and B. juncea genotypes. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2010;126:305–315

- Ahmadi MR, Nikkhah MJ, Aghajani MA, Ghobakhloo M. Morphological variability among Sclerotinia sclerotiorum populations associated with stem rot of important crops and weeds. World Appl Sci J. 2012;20(11):1561–1564.

- Zanatta TP, Stela MK, Caroline WG, Daniele CF, Daniela MELCB, Eduardo MT, Joao AP, Paola AB. Morphological and Pathogenic Characterization of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J Agril Sci. 2019; 11(8):302-313.

- Abreu GS, Grogn RG. Epidemiology of diseases caused by Sclerotinia species. Phytopathology. 2011; 69: 899-903.

- Ghasolia RP, Shivpuri A. Morphological and pathogenic vari-ability in rapeseed and mustard isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotio-rum. Indian Phytopathol. 2007;60:76–81.