More Information

Submitted: 04 June 2020 | Approved: 17 June 2020 | Published: 18 June 2020

How to cite this article: Arya V, Parmar RK. A Perspective on therapeutic potential of weeds. J Plant Sci Phytopathol. 2020; 4: 042-054.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jpsp.1001050

ORCiD ID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6808-1754

Copyright License: © 2020 Arya V, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: New Zealand; Phytoconstituents; Phytoremediation; Weeds

A Perspective on therapeutic potential of weeds

Vikrant Arya1* and Ranjeet Kaur Parmar2

1Assistant Professor, Government College of Pharmacy, Rohru, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India

2Home Maker, Pranav Kuteer, Jayanti Vihar, Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, India

*Address for Correspondence: Vikrant Arya, Assistant Professor, Government College of Pharmacy, Rohru, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh-171207, India, Tel: 8628998699; Email: [email protected]

Nature gives us a diverse plethora of floral wealth. Weeds have been recognized as invasive plant by most of scholars in today’s world with extraordinary travel history. They are considered to be noxious for adjoining plant species and also as economic hazard. Weeds inhabited in almost entire biomes and have capability to survive in harsh conditions of environment thereby become source of inspiration for finding novel phytoconstituents. Weeds play a significant role in absorbing harmful micro pollutants that are affecting ecosystem adversely. There are so many examples like canna lily, bladder wort, coltsfoot, giant buttercup etc. playing crucial part in sustaining environment. Different isolation and characterization approaches like high pressure liquid chromatography, gas chromatography, ion exchange chromatography, nuclear magnetic resonance, mass spectroscopy etc. have also been fetched for obtaining novel constituents from weeds. The main aim of this review is to analyze the therapeutic potential of weeds established in New Zealand and effort to unfold the wide scope of its applications in biological sciences. Upon exploration of various authorized databases available it has been found that weeds not only are the reservoir of complex phytoconstituents exhibiting diverse array of pharmacological activities but also provide potential role in environment phytoremediation. Phytoconstituents reported in weeds have immense potential as a drug targets for different pathological conditions. This review focuses on the literature of therapeutic potential of weeds established in New Zealand and tried to unveil the hidden side of these unwanted plants called weeds.

‘Horse Hoeing Husbandry’ named famous writing by Jethro Tull (1731) mentioned first time the word ‘weed’ [1]. Weeds may be considered as plants whose abundance must be over or above a specific level can cause major environmental concern [2]. Aldrich and Kremer, 1997 defined weed as a part of dynamic ecosystem [3]. Plant originated in natural environment and, in response to imposed or natural environments, evolved, and continues to do so, as an interfering associate with crops and activities. Weeds may interfere with the utilization of land and water resources thereby adversely affect human welfare [4]. According to Ancient Indian Literature earth is blessed with diverse flora and every existing plant has their own importance. Some plants are considered unwanted but they may have beneficial properties. Scholars are trying hard to explore the hidden potential of such unwanted plants [5]. Weeds have interactions with other organisms and some of these interactions can have direct effects on the functioning of agro-ecosystem [6]. They serve as an indirect resource for predatory species [7] and it could alternative food sources for organisms that play prominent role in insect control [8]. Weeds have a unique travel history. Clinton L. Evans in his book ‘The war on weeds in the prairie west- An Environmental History’ mentioned about travelling of weeds in ships, railways, automobiles from one country to another as food contaminants, animal feed, farm implements etc. during trade [9]. Weeds are firmly distributed and established all over New Zealand. Authors Ian Popay, Paul Champion and Trevor James in their book ‘An Illustrated Guide to Common Weeds of New Zealand’ (edition 3rd) published by New Zealand Plant Protection Society in 2010 mentioned the detailed description of around 380 weed species established in New Zealand [10]. Different scientific databases/ information resources (governmental, private, universities, initiatives, organizations etc.) of New Zealand extensively explored over a year as mentioned in table 1 to obtain data pertaining to weeds prevalent within geographical boundaries of New Zealand. After obtaining desired data of different weeds, a literature search was performed using the keyword ‘‘Name of weed (e.g. Aristea ecklonii) Pharmacology’’, ‘‘New Zealand plants’’, ‘‘weed pharmacology’’, ‘‘therapeutic weed’’ individually or all together in different scientific databases of Scopus, Web of Science and Pubmed to obtain therapeutic potential of weeds. Celastrus orbiculatus (Climbing spindle berry) [59], Robinia pseudoacacia (False acacia) [63], Daphne laureola (Green daphne laurel) [66], Glaucium flavum (Horned poppy) [70], Senecio latifolius (Pink ragwort) [80], Solanum nigrum (Black night shade) [86] have potent anticancer activities. Aristea ecklonii (Aristea) [50], Alocasia brisbanensis (Elephant ear) [62], Lycopus europaeus (Gypsywort) [68] exhibited antimicrobial activities. Pseudosasa japonica (Arrow bamboo) [51], Sambucus nigra (Elder) [61], Equisetum arvense (Field horsetail) [65] showed antioxidant effect. Hedera helix (Ivy) [72], Persicaria hydropiper (Mexican water lily) [75], Persicaria hydropiper (Water pepper) [106] showed anti-inflammatory properties. Weeds like Zantedeschia aethiopica (Arum lily) [112], Utricularia gibba (Bladderwort) [113], Canna indica (Canna lilly) [114], Tussilago farfara (Coltsfoot) [115], Egeria densa (Eregia) [116], Ranunculus acris (Giant buttercup) [117], Cytisus scoparius (Broom) [118], Poa annua (Annual poa) have prominent role in biomonitoring of heavy metals in multiple environments [119].

| Table 1: Description of scientific databases/ information resources of New Zealand for weed identification. | ||||

| PRIMARY INFORMATION SOURCES | SECONDARY INFORMATION SOURCES* | |||

| Source name | Source type | Authors | Web address | Database/information resource |

| An encyclopedia of New Zealand, 1966 | Encyclopedia | McLintock AH | http://www.agpest.co.nz | AgPest: It is an open access tool available for New Zealand farmers and agricultural professionals containing information about weeds, pest identification, their biology, impact and management |

| Common weeds in New Zealand, 1976 | Book | Parham BEV, Healy AJ |

http://www.agriculture.vic.gov.au | Agriculture victoria : Platform is used to promote agriculture industry in New Zealand and encompass information related to weeds and plant protection |

| Weeds in New Zealand protected natural areas: A review for the Department of Conservation, 1990 | Book | Williams PA, Timmins SM | http://www.cropscience.bayer.co.nz | Bayer crop science: It is one of the major information providers of crop protection products |

| Problem weeds on New Zealand islands, 1997 | Book ISBN 0-478-01885-1 |

Atkinson IAE | http://www.gw.govt.nz | Greater wellington university: It is a local government body in New Zealand represented by regional and territorial councils |

| New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research, 50(2), 2007 | Journal | Bourdot GW, Fowler SV, Edwards GR, Kriticos DJ, Kean JM, Rahman A, Parsons AJ |

http://www.learnz.org.nzs | Learnz: It is a initiative of free virtual field trips that help students to acquire inaccessible knowledge regarding various agricultural activities |

| Consolidated list of environmental weeds in New Zealand, 2008 | Journal ISBN 978–0–478–14412–3 |

Howell C | http://www.massey.ac.nz | Massey university: In Massey University, College of Sciences prepared a database dedicated to provide information regarding weeds in New Zealand |

| New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 33 (2), 2009 | Journal | Sullivan JJ, Williams PA, Timmins SM, Smale MC |

http://www.mpi.govt.nz | Ministry for primary industries: The Ministry for Primary Industries is dedicated to improving agriculture productivity, food safety, increasing sustainability and reducing biological risk |

| An illustrated guide to common weeds of New Zealand, 2010 | Book | Popay I, Champion P, James T |

http://www.nzpcn.org.nz | New Zealand plant conservation network: This network system is framed to conserve the floral wealth of New Zealand |

| New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 39(1), 2015 | Journal | McAlpine KG, Lamoureaux SL, Westbrooke I | http://www.ourbigbackyard.nz | Our big backyard: This aims to restore, create and maintain healthy habitats of New Zealand |

| Agronomy, 9, 2019 | Journal | Ghanizadeh H, Harrington KC | http://www.waikoregion.govt.nz | Waikato: This local government body works for maintaining agriculture resources and sustainability to ensure strong economy |

| Climate change risk assessment for terrestrial species and ecosystems in the Auckland region. Auckland Council, 2019 | Technical report ISBN 978-1-98-858966-4 |

Bishop C, Landers TJ |

http://www.weedbusters.org.nz | Weedbusters: Programme facilitates to eradicate weeds in New Zealand |

| *Secondary information resources/databases have been explored from March 2019 to March 2020 | ||||

Chemical profile of weeds established in New Zealand

Weeds established in New Zealand encompass wide array of therapeutic phytoconstituents. Weeds serve as biosynthetic factory for synthesis of phytochemicals. They are sources of rich medicinal wealth which includes primary metabolites (polysaccharides) and secondary metabolites (alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, tannins, volatile oils etc.). They are the potential sources of complex phytoconstituents. Selaginella kraussiana (African club moss) [11], Lonicera japonica (Japnese honeysuckle) [32], Eriobotrya japonica (Loquat) [35] and Anredera cordifolia (Mignonette vine) [38] contains polysaccharides. Alternanthera philoxeroides (Alligator weed) [13] and Rhamnus alaternus (Evergreen buckthorn) [26] contains anthraquinone glycosides. Lamium galeobdolon (Artillery plant) [14] and Heracleum mantegazzianum (Giant hogweed) [27] contains appreciable amount of volatile oil. Modern spectroscopic methods have been explored for structural elucidation of bioactive constituents present in weeds. LC-MS has been used for quantitative detection of xyloglucan oligosaccharide in Selaginella kraussiana [11], betulonic acid in Alnus glutinosa (Black alder) [12], jasmonic acid in Drosera capensis (Cape sundew) [20], flavonoids in Gunnera tinctoria (Chilean rhubarb) [24], pyrrolizidine alkaloid esters in Gymnocoronis spilanthoides (Senegal tea) [42]. NMR employed for characterization of compounds present in Fraxinus excelsior (Ash) [15], Berberis glaucocarpa (Barberry) [17], Ligustrum sinense (Chinese privet) [25], Rhamnus alaternus [26], Cestrum parqui (Green cestrum) [30], Ranunculus sardous (Hairy buttercup) [49]. Detailed summary of chemical compounds isolated from weeds established in New Zealand indicated in table 2.

| Table 2: A summary of compounds isolated from weeds established in New Zealand. | |||||

| Common name | Botanical name | Native of | Compound reported | Analytical approach adopted | References |

| African club moss | Selaginella kraussiana Selaginellaceae |

Africa | Xyloglucan oligosaccharide | Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (MS), high performance anion exchange chromatography | [11] |

| Black alder | Alnus glutinosa Betulaceae |

Eurasia, Africa | Betulin, betulinic acid, betulonic acid, lupeol | Desorption atmospheric pressure photoionization (MS) | [12] |

| Alligator weed | Alternanthera philoxeroides Amaranthaceae |

South America | Anthraquinone glycosides | Spectral analysis | [13] |

| Artillery plant | Lamium galeobdolon Lamiaceae |

Europe, Asia | Volatile compounds | GC-MS | [14] |

| Ash | Fraxinus excelsior Oleaceae |

Europe, Asia, Africa | Nodulisporiviridin M | ID, 2D 1H & 13C NMR | [15] |

| Asiatic knotweed | Fallopia japonica Polygonaceae |

Asia | Carotenoid | HPTLC, HPLC-MS | [16] |

| Barberry | Berberis glaucocarpa Berberidaceae |

Himalayas | Bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloid, oxyacanthine | 1D, 2D NMR | [17] |

| Blackberry | Rubus fruticosus Rosaceae |

North temperate regions | Polyunsaturated fatty acids | Supercritical carbon dioxide method | [18] |

| Boxthorn | Lycium ferocissimum Solanaceae |

South Africa | Betaine | Fast atom bombardment mass spectroscopy | [19] |

| Cape sundew | Drosera capensis Droseraceae |

South Africa | Jasmonic acid | LC-MS/MS | [20] |

| Castor oil | Ricinus communis Euphorbiaceae |

Africa, Eurasia | Ricin | Spectral analysis | [21] |

| Century plant | Agave americana Agavaceae |

Mexico | Fructans | Thermogravimetric analysis | [22] |

| Cherry laurel | Prunus laurocerasus Rosaceae |

South East Europe | Cyanogenetic glycosides, benzoic acid derivative | LC-ESIMS | [23] |

| Chilean rhubarb | Gunnera tinctoria Gunneraceae |

South America | Flavonoids | HPLC-MS/MS | [24] |

| Chinese privet | Ligustrum sinense Oleaceae |

China |

10-hydroxyl-oleuropein, 3-O-alpha-L-rhamnopyranosyl-kaempherol-7-O-beta-D-glucopyranoside | 1D, 2D NMR | [25] |

| Evergreen buckthorn | Rhamnus alaternus Rhamnaceae |

Mediterranean region | Anthraquinone glycosides | 1D, 2D NMR, FAB-MS |

[26] |

| Giant hogweed | Heracleum mantegazzianum Apiaceae |

Eurasia | Essential oil | GC-MS | [27] |

| Giant knotweed | Fallopia sachalinensis Polygonaceae |

Asia | Olymeric procyanidins, flavones, flavonoids | GC-MS | [28] |

| Giant reed | Arundo donax Gramineae |

Eurasia | Bis-indole alkaloid, phenylpropanoid | Spectral analysis | [29] |

| Green cestrum | Cestrum parqui Solanaceae |

Chile, Peru | Saponin | 1H, 13C NMR | [30] |

| Heather | Calluna vulgaris Ericaceae |

Europe | Catechin, epicatechin | HPLC-DAD-ESI/MS | [31] |

| Japnese honeysuckle | Lonicera japonica Caprifoliaceae |

Japan | Polysaccharides | HPLC, FTIR | [32] |

| Khasia berry | Cotoneaster simonsii Rosaceae |

China | Tocopherols | Spectral analysis | [33] |

| Kudzu vine | Pueraria lobata Fabaceae |

Japan | Lobatamunsolides A-C, norlignans | LC-MS | [34] |

| Loquat | Eriobotrya japonica Rosaceae |

China, Japan | Polysaccharides | UMAE | [35] |

| Manchurian rice grass | Zizania latifolia Poaceae |

China | Proanthocyanidins | UAE | [36] |

| Mexican devil | Ageratina adenophora Asteraceae |

South America | Thymol derivatives | 1H NMR, HR-ESI-MS, IR | [37] |

| Mignonette vine | Anredera cordifolia Basellaceae |

South America | Water soluble polysaccharides | UV, FTIR | [38] |

| Moth plant | Araujia hortorum Asclepiadaceae |

Brazil, Argentina | Protease (araujiain) | Ultracentrifugation, ion exchange chromatography, MS | [39] |

| Mysore thorn | Caesalpinia decapetala Fabaceae |

Asia | Cassane type furanoditerpenoids | HPLC, 1D NMR, 2D NMR, HRESIFTMS | [40] |

| Plectranthus | Plectranthus ciliates Lamiaceae |

South Africa | Anthocyanins | UV | [41] |

| Senegal tea | Gymnocoronis spilanthoides Asteraceae |

Mexico | Pyrrolizidine alkaloid esters | HPLC, MS-MS | [42] |

| Tree of heaven | Ailanthus altissimia Simaroubaceae |

China | Phenlypropanoids | NMR, HRESIMS | [43] |

| Tuber ladder fern | Nephrolepis cordifolia Davalliaceae |

Australia | 2,4-hexadien-1-ol, nonanal, thymol | GC-MS | [44] |

| White bryony | Bryonia cretica Cucurbitaceae |

Eurasia | Cucurbitane type triterpene | Bioassay guided fractionation, NMR | [45] |

| Bracken | Pteridium esculentum Dennstaedtiaceae |

Australia | Ptesculentoside, caudatoside, ptaquiloside | LC-MS | [46] |

| Catsear | Hypochaeris radicata Asteraceae |

Eurasia | Lignans, sesquiterpene lactones | NMR, HRMS | [47] |

| Creeping buttercup | Ranunculus repens Ranunculaceae |

Europe, Asia | Methyl 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoate | 1D, 2D NMR | [48] |

| Hairy buttercup | Ranunculus sardous Ranunculaceae |

Europe, Asia | Ranunculin | TLC, HPTLC | [49] |

Therapeutic potential of weeds established in New Zealand

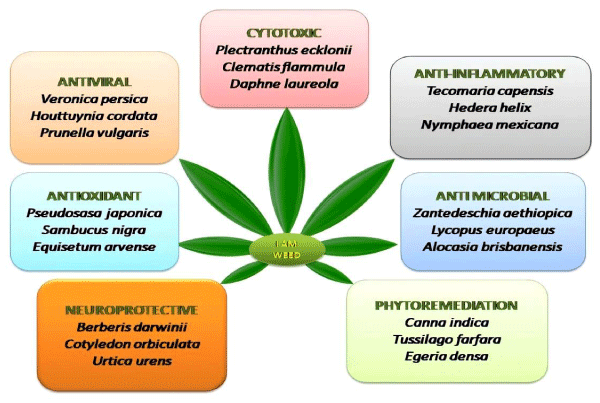

Weeds have been explored for diverse pharmacological actions like anti cancer, anti microbial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiviral etc. as mentioned in table 3 and figure 1.

| Table 3: A summary of pharmacological activities exhibited by weeds. | |||||

| Common name | Botanical name | Native of | Reported pharmacological activity | Outcome of study | Reference |

| Aristea | Aristea ecklonii Iridaceae |

West and South Africa | Antimicrobial | Plumbagin isolated from plant exhibited antimicrobial activities with MIC 2 µg/ml and 16 µg/ml | [50] |

| Arrow bamboo | Pseudosasa japonica Poaceae |

Japan, South Korea | Antioxidant | Leaves extract has potential to ameliorate oxidative stress by improving antioxidant activity | [51] |

| Bear’s breeches | Acanthus mollis Acanthaceae |

South West Europe | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory | Ethanol extract inhibited NO production | [52] |

| Blue spur flower | Plectranthus ecklonii Lamiaceae |

South Africa | Against pancreatic cancer | Antiproliferative effect was found to be effective against BxPC3, PANC-1, Ins1-E, MICF-7, HaCat, Caco-2 cell lines | [53] |

| Buddleia | Buddleja davidii Buddlejaceae |

China | AChE inhibitory activity | Linarin isolated from plant inhibit AChE activity | [54] |

| Cape honeysuckle | Tecomaria capensis Bignoniaceae |

South Africa | Analgesic, antipyretic, anti-inflammatory activities | Methanolic extract of leaves significantly prevented increase in volume of paw edema | [55] |

| Cat’s claw creeper | Macfadyena unguis-cati Bignoniaceae |

Central and South America | Anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic | Crude ethanol extract exhibited marked anti-inflammatory and cytotoxicity against lung cancer cell line | [56] |

| Chocolate vine | Akebia quinata Lardizabalaceae |

China, Korea, Japan | Anti-fatique agent | Akebia extract showed marked improvement in lethargic behavioral test | [57] |

| Clematis | Clematis flammula Ranunculaceae |

Southern Europe and Northern Africa | Cytotoxic | Weed extract cause kinases and transcription factor induction | [58] |

| Climbing spindle berry | Celastrus orbiculatus Celastraceae |

Eastern Asia, Korea, Japan, China | Against gastric cancer | Compound 28-hydroxy-3-oxoolean-12-en-29-oic acid inhibited the migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells | [59] |

| Darwin’s barberry | Berberis darwinii Berberidaceae |

Chile, Argentina | Alzheimer’s disease | Methanolic extract of stem bark exhibited acetylcholinestrase inhibitory activity | [60] |

| Elder | Sambucus nigra Caprifoliaceae |

Europe, West Asia, North Africa | Antioxidant | Free radical scavenging potential | [61] |

| Elephant ear | Alocasia brisbanensis Araceae |

Ceylon, Tahiti | Antimicrobial | Extract showed promising antimicrobial activities against Staphylococcus aureus | [62] |

| False acacia | Robinia pseudoacacia Fabaceae |

South Eastern USA | Antitumor | Inhibition of IL-1β signaling | [63] |

| False tamarisk | Myricaria germanica Tamaricaceae |

Eurasia | Cytotoxic | Compound tamgermanitin exhibited potent anti cancer effect | [64] |

| Field horsetail | Equisetum arvense Equisetaceae |

Temperate Northern Hemisphere | Antioxidant | Potent antioxidant in DPPH assay | [65] |

| Green daphne laurel | Daphne laureola Thymelaeaceae |

North Africa, South West Europe | Anticancer | Cytotoxic against lung cancer | [66] |

| Green goddess | Zantedeschia aethiopica Araceae |

South Africa | Antimicrobial | Peptides in weed exhibited antimicrobial activities | [67] |

| Gypsywort | Lycopus europaeus Lamiaceae |

Europe, Asia | Antimicrobial | Compound euroabienol showed broad spectrum activity | [68] |

| Hop | Humulus lupulus Cannabaceae |

Europe, Western Asia, North America | Osteogenic | Activity evaluated via MC3T3-E1 cells lines | [69] |

| Horned poppy | Glaucium flavum Papaveraceae |

Western Europe, South Western Asia | Against breast cancer | Bocconoline compound isolated from the plant inhibit viability of cancer cells | [70] |

| Houttuynia | Houttuynia cordata Saururaceae |

Asia | Antiviral | Houttuynoid B isolated from the weed prevents cell entry of Zika virus | [71] |

| Ivy | Hedera helix Araliaceae |

Europe, North Africa | Anti-inflammatory | Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus strain | [72] |

| Jerusalem cherry | Solanum pseudocapsicum Solanaceae |

South America | Acetylcholinestrase inhibitor | Alkaloids reported in the plant exhibited AChE inhibition | [73] |

| Lantana | Lantana camara Verbenaceae |

Tropical America | Sedative | Essential oil from weed possess CNS depressant effects | [74] |

| Mexican water lily | Nymphaea mexicana Nymphaeaceae |

Mexico | Anti-inflammatory | Cox-2 inhibition | [75] |

| Nasturtium | Tropaeolum majus Tropaeolaceae |

Europe, America, Africa, Asia | Antimicrobial | Compound 3-[3-pyridinyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl] benzonitrile exhibited potent antimicrobial activities | [76] |

| Needlebush | Hakea sericea Proteaceae |

Australia | Cytotoxic | Extract inhibited MCF-7 cell line | [77] |

| Old man’s beard | Clematis vitalba Ranunculaceae |

Europe, South West Asia | Antinociceptive and antipyretic | Vitalboside isolated from weed exerted action | [78] |

| Pig’s ear | Cotyledon orbiculata Crassulaceae |

Africa | Anticonvulsant | Aqueous and methanolic extracts showed prominent effects on gabaergic and glutaminergic mechanisms | [79] |

| Pink ragwort | Senecio latifolius Asteraceae |

South Africa | Cytotoxic | Cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells caused depletion of cellular GSH | [80] |

| Rough horsetail | Equisetum hyemale Equisetaceae |

Temperate Northern Hemisphere |

Antitrypanosomal | n-butanol fraction exert antiprotozoal effect | [81] |

| Royal fern | Osmunda regalis Osmundaceae |

Europe, India, Africa | Inhibition of head and neck cancer cell proliferation | Extract revealed growth inhibiting effect on HLaC78 and FaDu | [82] |

| Tree privet | Ligustrum lucidum Oleaceae |

China | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Inactivation of PL3K/Akt pathway | [83] |

| Tutsan | Hypericum androsaemum Clusiaceae |

South and Western Europe | Anti-lipid peroxidation | n-hexane fraction exerted desired activity | [84] |

| Chingma lantern | Abutilon theophrasti Malvaceae |

Temperate region | Antibacterial | Extract showed activity against Staphylococcus aureus | [85] |

| Black night shade | Solanum nigrum Solanaceae |

North Western Africa | Antitumor | Active against breast cancer cell line MCF7 | [86] |

| Broad leaved dock | Rumex obtusifolius Polygonaceae |

Eurasia | Hypoglycemic | Ethanolic extract improved glucose tolerance in rabbits | [87] |

| Broad leaved fleabane | Conyza sumatrensis Asteraceae |

South America | Antiplasmodial | Study confirmed the traditional use of weed | [88] |

| Broad leaved plantain | Plantago major Plantaginaceae |

Eurasia | Potential wound healer | Showed activity against hyaluronidase and collangenase enzymes | [89] |

| Chick weed | Stellaria media Caryophyllaceae |

India | Antifungal | Peptides in weed were responsible for its potent activity | [90] |

| Cleavers | Galium aparine Rubiaceae |

Temperate zone | Immunomodulator | Ethanolic extract stimulated immunocompetent blood cells | [91] |

| Dandelion | Taraxacum officinale Asteraceae |

Africa | Antioxidant | Extract from leaf provide protection against free radical mediated oxidative stress | [92] |

| Father | Chenopodium album Amaranthaceae |

Temperate zone | Antioxidant | Weed showed protection against mercury induced oxidative stress | [93] |

| Galinsoga | Galinsoga parviflora Asteraceae |

Tropical America | Photocarcinogenesis | Caffeic acid derivative protect dermal UVA-induced oxidative stress | [94] |

| Hedge mustard | Sisymbrium officinale Brassicaceae |

Southern Europe | Inhibition of oxidative mutagenicity | Polyphenols in weed exhibited desired action | [95] |

| Hemlock | Conium maculatum Apiaceae | Temperate region | Antimicrobial | Essential oils reported in weed showed activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa | [96] |

| Manuka | Leptospermum scoparium Myrtaceae |

New Zealand, South East Australia | Antibacterial | Oils exhibited activity against gram negative pathogens | [97] |

| Nettle | Urtica urens Urticaceae |

Europe | Anxiolytic | Extract increased the time spent in bright-lit chamber of light/dark box pharmacological model | [98] |

| Pennyroyal | Mentha pulegium Lamiaceae |

Northern Africa | Antidiabetic | Aqueous extract revealed improvement of glucose tolerance in in-vivo rat model | [99] |

| Red dead nettle | Lamium purpureum Lamiaceae |

Eurasia | Haemostatic activity | Extracts showed promising results in haemostatic test | [100] |

| Scarlet pimpernel | Anagallis arvensis Primulaceae |

Northern Africa | Molluscicidal | Aqueous leaf extract showed activity against Schistosoma mansoni | [101] |

| Scotch thistle | Cirsium vulgare Asteraceae |

Europe | Hepatoprotective | Hexane extract showed anti-necrotic and anti-cholestatic effects | [102] |

| Scrambling speedwell | Veronica persica Plantaginaceae |

Eurasia, America | Antiviral | Extract showed synergistic activity in combination with acyclovir anti-HSV therapy | [103] |

| Selfheal | Prunella vulgaris Lamiaceae |

Eurasia, America | Inhibition of IHNV infection | Ursolic acid decrease cytopathic effect and viral titer | [104] |

| Sow thistle | Sonchus oleraceus Asteraceae |

Asia | Nephroprotective | Extract showed desired effect by inhibiting ischemia reperfusion in rats | [105] |

| Water pepper | Persicaria hydropiper Polygonaceae |

Eurasia | Anti-inflammatory | Extract showed desired therapeutic effect | [106] |

| Yarrow | Achillea millefolium Asteraceae |

Eurasia, North America | Antibabesial activity | Different extract were active against Brucella canis | [107] |

| Woolly mullein | Verbascum thapsus Scrophulariaceae |

Eurasia | Antimicrobial | Ethanolic extract were potent against gram positive bacteria | [108] |

| Wild teasel | Dipsacus fullonum Caprifoliaceae |

Australia | Antibacterial | Compounds isolated from root exhibited activity against Staphylococcus aureus | [109] |

| Cocklebur | Xanthium strumarium Asteraceae |

Temperate zone | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Weed induce apoptosis in HCC cell lines in a dose dependent manner | [110] |

Figure 1: Therapeutic potential of weeds.

Anticancer weeds: Some important cytotoxic weeds include Clematis flammula [58], Hakea sericea (Needlebush) [77], Robinia pseudoacacia (False acacia) [63], Daphne laureola [66]. Myricaria germanica (False tamarisk) [64], Senecio latifolius (Pink ragwort) [80]. Osmunda regalis (Royal fern) [82]. Parvifloron D isolated from Plectranthus ecklonii via flash dry column chromatography exhibited antiproliferative effects against pancreatic cancer when evaluated against HaCat, BxPC3, Caco-2, MCF-7, Ins1-E and PANC-1 cell lines [53]. Aqueous extract of weed Solanum nigrum at concentration of 10 g/l caused 43% cytotoxicity in MCF7 cell line by inhibiting migration, suppression of hexokinase and pyruvate kinase [86]. Triterpene (28-Hydroxy-3-oxoolean-12-en-29-oic acid) present in Celastrus orbiculatus showed inhibitory activity on SGC-7901 and BGC-823 cells lines [59]. Bocconoline alkaloid isolated from dried roots of Glaucium flavum (Horned poppy) exhibited cytotoxicity with IC50 value of 7.8µM [70].

Antimicrobial weeds: Invasive weed Aristea ecklonii containing Plumbagin exhibited antimicrobial activity with minimum inhibitory concentration between 2 μg/ml and 16 μg/ml [50]. Antimicrobial peptides isolated from arum lily (Zantedeschia aethiopica) exhibited potent antimicrobial activity [67]. Euroabienol (abietane-type diterpenoid) isolated from fruits of Lycopus europaeus exhibited broad spectrum antimicrobial activity [68]. Compounds 3-[3-(3-pyridinyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl] benzonitrile and [3,5-Bis (1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-hydroxyphenyl] isolated from weed Tropaeolum tuberosum when tested against Candida tropicalis exhibited antifungal activities with MICs of 100 μM and 50 μM [76]. Extracts obtained from leaves of weed Abutilon theophrasti elicit antimicrobial potential against Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella, Streptococcus and E. coli species [85]. Essential oils isolated from weeds Conium maculatum, Leptospermum scoparium showed antimicrobial activity against several strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [96,97]. Ethanolic extracts of woolly mullein reported positive against gram positive bacteria (Bacillus cereus) [108]. Phenolic compounds from Dipsacus fullonum exerted inhibitory effects on Staphylococcus aureus DSM 799 and E. coli ATCC 10536 strains [109].

Antioxidant weeds: Strong antioxidant activity was reported by ferulic acid derived from leaves of weed Pseudosasa japonica when evaluated using DPPH (54 %) and ABTS (65 %) [51]. Antioxidant potential of Taraxacum officinale was determined using in vitro methods (DPPH, ABTS, FRAP). The ABTS method reveled that antioxidant activity was 156±5.28 µg/ml [92]. Other potential antioxidant weed includes Acanthus mollis [52], Sambucus nigra [61], Equisetum arvense [65].

Anti-inflammatory weeds: A study by Akhtar, et al. 2019 investigated the anti-inflammatory properties of Hedera helix and its major compounds on Staphylococcus aureus induced inflammation in mice. Hederacoside-C isolated from weed exerted profound anti-inflammatory effects [72]. Mexican water lily (Nymphaea mexicana) was found to be potent COX-2 inhibitor [75]. Active compounds isolated from aerial parts of weed Clematis vitalba when evaluated in vivo against carrageenan, serotonin, PGE-2 induced hind paw edema showed antinociceptive and antipyretic effects [78]. Methanolic extract of leaves of Tecomaria capensis significantly prevented increase in volume of paw edema [55]. Extract of Persicaria hydropiper exerted marked anti-inflammatory effects [106]. Aqueous extract alongwith compounds (calceorioside B, homoplantaginin, plantamajoside) isolated from the aerial parts of Plantago major showed inhibition against hyaluronidase enzyme [89].

Antiviral weeds: Methanolic extract of scrambling speedwell weed (Veronica persica) reported potent activity against herpes simplex viruses and synergistic activity in combination with acyclovir anti-HSV therapy [103]. Ursolic acid isolated form weed Prunella vulgaris inhibited IHNV infection in aquaculture with an inhibitory concentration of 99.3 % at 100 mg/l [104].

Weeds acting on CNS: Methanolic extract of stem bark of darwin’s barberry (Berberis darwinii) inhibited acetylcholinestrase in vitro with IC50 value of 1.23 ± 0.05 microg/mL thereby provide relief in alzheimer’s disease [60]. Alkaloid solanocapsine isolated from weed Solanum pseudocapsicum reported to inhibit activity of enzyme acetylcholinestrase [73]. Nettle (Urtica urens) exhibited anxiolytic activity in mice when evaluated using hole board test, light-dark box test and rota rod test. Extract showed increased head-dip duration and head-dip counts in hole board test [98]. Aqueous (50-400 mg/kg i.p.) and methanolic extracts (100-400 mg/kg i.p.) of Pig’s ear (Cotyledon orbiculata) exhibited anticonvulsant activity which predominantly delayed onset of seizures induced by N-methyl-dl-aspartic, bicuculline, picrotoxin in mice models [79].

Other pharmacological activities of weeds: Aqueous extract of Akebia quinata showed positive effect against fatigue in mice exposed to chronic restraint stress when evaluated using forced swimming behavioral test, sucrose preference and open field tests [57]. n-butanol fraction of weed Equisetum hyemale exerted antiprotozoal effects against Trypanosoma evansi trypomastigotes after nine hours exposure [81]. Chen, et al. 2019 reported osteogenic activities of Humulus lupulus in MC3T3-E1 cell lines [69]. Ethanolic extract of weed Galium aparine stimulated the transformational activity of immunocompetent blood cells in vitro [91]. Aqueous extract of aerial parts of Mentha pulegium (20 mg/kg) showed antihyperglycemic effect by marked improvement in oral glucose tolerance test in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats [99]. Butanolic extracts of aerial parts of Lamium album and Lamium pupureum showed haemostatic activity in wistar rats when evaluated by tail bleeding time determination and acenocoumarol carrageenan test compared to vitamin K [100]. Anagallis arvensis (Scarlet pimpernel) leaf extract showed molluscicidal activity against Biomphalaria alexandrina at LC50 37.9 mg/l and LC90 48.3 mg/l [101]. Hexane extract rich in lupeol acetate of weed scotch thistle (Cirsium vulgare) prevented carbon tetrachloride induced liver damage in rats by diminishing lipid peroxidation and nitric oxide levels [102]. Extracts of Sonchus oleraceus (Sow thistle) were reported to be nephroprotective against kidney ischemia reperfusion injury in wistar rats [105]. Water extract, ethanol extract, hexane/acetone extract obtained from Achillea millefolium (Yarrow) were effective against Babesia canis parasite at 2 mg/ml concentration [107].

Other potential applications of weeds established in New Zealand

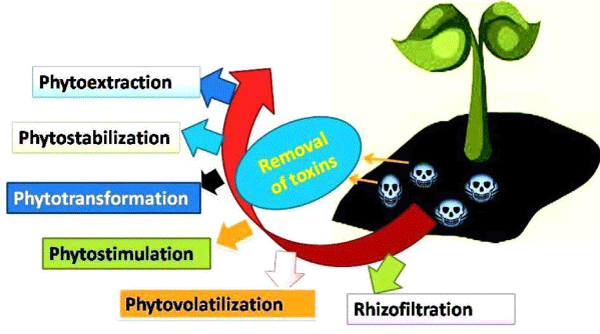

A large number of weed communities has been reported to clean environment through phytoremediation process and act as bioindicators (Figure 2). Phytoremediation is described as a process of eradicating toxic contaminants from soil, water and air. This process involves phytoextraction (harvesting of biomass), phytostabilization (contaminants stabilized into less toxic compounds), phytotransformation (chemical modification of contaminants), phytostimulation (rhizosphere degradation), phytovolatilization (conversion of toxic compounds into volatile form) and rhizofiltration (filtration through roots) [111]. Arum lily (Zantedeschia aethiopica) acts as micropollutant removal by removing accumulation of copper, zinc, carbamazepine and linear alkylbenxene sulphonates [112]. Bladderwort (Utricularia gibba) [113], canna lilly (Canna indica) [114], coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara) [115], egeria (Egeria densa) [116], giant buttercup (Ranunculus acris) [117], broom (Cytisus scoparius) [118], annual poa (Poa annua) have been involved in removing toxic metals (chromium, cadmium, zinc, lead) from the environment [119]. Parrot feather (Myriophyllum aquaticum) aids in removing antibiotic (tetracycline) from water [120]. Oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) potentiated crude oil phytoremediation and used in eliminating pollution from environment [121]. Apart from these properties weeds have also been found to be employed in other industries e.g. buffalo grass weed (Stenotaphrum secundatum) used in turf grass industry [122]. Mucoadhesive properties of water soluble gum obtained from Hakea gibbosa added in sustained release dosage forms [123]. Silver nanoparticles having average particle size 20 nm synthesized from Cestrum nocturnum showed more antioxidant potential as compared to vitamin C alongwith strong antibacterial activity against Vibrio cholerae with MIC of 16 µg/ml [124]. Organic fertilizer manufactured via aquatic weed Salvinia molesta when evaluated using FT-IR, plant bioassay test for determination of its fertilizer value and chemical composition showed promising results as vermicompost [125]. Eragrostis species (E. capensis, E. curvula) and grass Stenotaphrum secundatum exhibited drought resistant ability [126,127].

Figure 2: An overview of Phytoremediation process.

Besides the therapeutic potential exhibited by weeds, toxicity profile should be taken into consideration while exploring them. Equisetum arvense (Field horsetail) exerted hepatotoxicity in rats [128], weeds like Zantedeschia aethiopica (Arum lily), Conium maculatum (Hemlock), Solanum nigrum (Black night shade) are considered poisonous in New Zealand [129]. Hedera helix (Ivy) caused contact dermatitis [130], Lantana camara exerted in vivo cell toxicity [131], Xanthium strumarium (Cocklebur) responsible for causing poisoning in cattle [132].

Humans define weeds as per their appropriateness and understanding of the plant. A plant investigated as weed in some region may be a plant of medicinal importance for another region. The usefulness of weeds has been ignored by humans for long time because of their invasive growth, competitors of genuine crop and no economic value. This human behaviour might be developed over time due to lack of proper knowledge of phytochemical screening as well as therapeutic potential of weeds. Weeds are the sources of human food, fodder in agriculture, shelter for some animals, helpful against soil erosion, indicators of soil nutrients, as well as sources of commercially important essential oils. In this era weeds have been extensively explored for their immense phytopharmacological prospects. It is evidenced that weeds have been sources of potential targets for different pathological conditions. However there is need of more scientific and clinical investigations required in assessment of toxicity profile to get the maximum potential of weeds. Weeds have protective role in environment as a component of phytoremediation and for sustainable ecosystem. Because of immense therapeutic potential implicit by weeds a new chain of thoughts emerge in our mind to consider the value of these important plants so called ‘weeds’. Are they need to be redefined or we need to rethink the concept of weeds? It is clear from the studies documented in this review that the approach of whether a plant is wanted or not should depends on its pharmacological potential and role in ecosystem other than merely the competitive effect of plant with the particular crop. Further advancements are required in order to spin the concept of weeds into therapeutic weeds.

| Important abbreviations used | ||

| ABTS | = | 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| COX | = | Cyclooxygenase |

| DPPH | = | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ESI | = | Electrospray ionization |

| FAB | = | Fast atom bombardment |

| FRAP | = | Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching |

| FTIR | = | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GC | = | Gas chromatography |

| GSH | = | Glutathione |

| HepG2 | = | Hepatoblastoma cells |

| HPLC | = | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| HPTLC | = | High-performance thin-layer chromatography |

| HRESIFTMS | = | High resolution electrospray ionization fourier transform mass spectrometry |

| HR-ESI-MS | = | High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry |

| HSV | = | Herpes simplex virus |

| IC50 | = | Inhibitory concentration |

| IHNV | = | Infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus |

| LC-ESIMS | = | Liquid chromatography electrospray ionisation mass spectroscopy |

| MCF7, SGC-7901, BGC-823 cells, BxPC3, PANC-1, Ins1-E, MICF-7, HaCat, Caco-2, HCC, HLaC78, FaDu | = | Cancer cell lines |

| MS | = | Mass spectroscopy |

| NMR | = | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| NO | = | Nitric oxide |

| PGE-2 | = | Prostaglandin E2 |

| TLC | = | Thin layer chromatography |

| UAE | = | Ultrasound-assisted extraction |

| UV | = | Ultraviolet spectroscopy |

| UVA | = | Ultra violet radiation |

- Jethro Tull. Horse hoeing husbandary, Berkshire. MDCC, 33; 1731.

- Crawley MJ. Biodiversity. In: Crawley, M.J., (ed.) Plant Ecology, 2nd Edn. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford; 1997.

- Aldrich RJ, Kremer RJ. Principles in weed management. Iowa State University Press; 1997.

- Rao VS. Principles of Weed Science, 2nd Edn, Science Publishers, Enfield, New Hampshire, USA; 2000.

- Oudhia P. Medicinal weeds in rice fields of Chhattisgarh, India. International Rice Research Notes. 1999; 24:40.

- Gibbons DW, Bohan DA, Rothery P, Stuart RC, Haughton AJ, et al. Weed seed resources for birds in fields with contrasting conventional and genetically modified herbicide-tolerant crops. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2006; 273: 1921-1928. PubMed: PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16822753

- Hawes C, Haughton AJ, Bohan DA, Squire GR. Functional approaches for assessing plant and invertebrate abundance patterns in arable systems. Basic and Applied Ecology. 2009; 10: 34-42.

- Kromp B. Carabid beetles in sustainable agriculture: a review on pest control efficacy, cultivation impacts and enhancement. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 1999; 74: 187-228.

- Evans CL. The war on weeds in the Prairie west: an environmental history. University of Calgary Press; 2002.

- Popay I, Champion P, James T. An Illustrated Guide to Common Weeds of New Zealand. 3rd Edn. New Zealand Plant Protection Society. 2010.

- Hsieh YS, Harris PJ. Structures of xyloglucans in primary cell walls of gymnosperms, monilophytes (ferns sensu lato) and lycophytes. Phytochemistry. 2012; 79: 87-101.

- Rasanen RM, Hieta JP, Immanen J, Nieminen K, Haavikko R, et al. Chemical profiles of birch and alder bark by ambient mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2019; 411: 7573-7583.

- Collett MG, Taylor SM. Photosensitising toxins in alligator weed (Alternanthera philoxeroides) likely to be anthraquinones. Toxicon. 2019; 167: 172-173. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31226258

- Alipieva K, Evstatieva L, Handjieva N, Popova S. Comparative analysis of the composition of flower volatiles from Lamium L. species and Lamiastrum galeobdolon Heist. ex Fabr. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung C. 2003; 58: 779-782.

- Masi M, Di Lecce R, Tuzi A, Linaldeddu BT, Montecchio L, et al. Hyfraxinic Acid, a Phytotoxic Tetrasubstituted Octanoic Acid, Produced by the Ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) Pathogen Hymenoscyphus fraxineus Together with Viridiol and Some of Its Analogues. J Agric Food Chem. 2019; 67: 13617-13623. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31661270

- Metlicar V, Vovk I, Albreht A. Japanese and Bohemian Knotweeds as Sustainable Sources of Carotenoids. Plants. 2019; 8: 384. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6843863/

- Alamzeb M, Omer M, Ur-Rashid M, Raza M, Ali S, et al. NMR, Novel Pharmacological and In Silico Docking Studies of Oxyacanthine and Tetrandrine: Bisbenzylisoquinoline Alkaloids Isolated from Berberis glaucocarpa Roots. J Anal Methods Chem. 2018; 7692913. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29888027

- Kitryte V, Narkeviciute A, Tamkute L, Syrpas M, Pukalskiene M, et al. Consecutive high-pressure and enzyme assisted fractionation of blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L.) pomace into functional ingredients: Process optimization and product characterization. Food Chem. 2020; 312: 126072. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31893552

- Weretilnyk EA, Bednarek S, McCue KF, Rhodes D, Hanson AD. Comparative biochemical and immunological studies of the glycine betaine synthesis pathway in diverse families of dicotyledons. Planta. 1989; 178: 342-352.

- Mithofer A, Reichelt M, Nakamura Y. Wound and insect‐induced jasmonate accumulation in carnivorous Drosera capensis: two sides of the same coin. Plant Biol. 2014; 16: 982-987. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24499476

- Małajowicz J, Kusmirek S. Structure and properties of ricin–the toxic protein of Ricinus communis. Postepy Biochemii. 2019; 65: 03-108. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31642648

- Cruz-Salas CN, Prieto C, Calderon-Santoyo M, Lagarón JM, Ragazzo-Sanchez JA. Micro-and Nanostructures of Agave Fructans to Stabilize Compounds of High Biological Value via Electrohydrodynamic Processing. Nanomaterials. 2019; 9:1659. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31766573

- Sendker J, Ellendorff T, Holzenbein A. Occurrence of benzoic acid esters as putative catabolites of prunasin in senescent leaves of Prunus laurocerasus. J Nat Prod. 2016; 79: 1724-1729. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27331617

- Bridi R, Giordano A, Penailillo MF, Montenegro G. Antioxidant Effect of Extracts from Native Chilean Plants on the Lipoperoxidation and Protein Oxidation of Bovine Muscle. Molecules. 2019; 24: 3264. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31500282

- Ouyang MA, He ZD, Wu CL. Anti-oxidative activity of glycosides from Ligustrum sinense. Natural product research. 2003; 17: 381-387. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14577686

- Ben Ammar R, Miyamoto T, Chekir-Ghedira L, Ghedira K, Lacaille-Dubois MA. Isolation and identification of new anthraquinones from Rhamnus alaternus L and evaluation of their free radical scavenging activity. Natural product research. 2019; 33: 280-286. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29533086/

- Matouskova M, Jurova J, Grulova D, Wajs-Bonikowska A, Renco M, Sedlak V, Poracova J, Gogalova Z, Kalemba D. Phytotoxic Effect of Invasive Heracleum mantegazzianum Essential Oil on Dicot and Monocot Species. Molecules. 2019; 24: 425. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6384721/

- Lachowicz S, Oszmianski J. Profile of Bioactive Compounds in the Morphological Parts of Wild Fallopia japonica (Houtt) and Fallopia sachalinensis (F. Schmidt) and Their Antioxidative Activity. Molecules. 2019; 24: 1436. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30979044

- Liu QR, Li J, Zhao XF, Xu B, Xiao XH, et al. Alkaloids and phenylpropanoid from Rhizomes of Arundo donax L. Natural Product Res. 2019: 1-6.

- Ikbal C, Habib B, Hichem BJ, Monia BH, Habib BH, et al. Purification of a natural insecticidal substance from Cestrum parqui (Solanaceae). Pak J Biol Sci. 2007; 10: 3822-3828. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19090236

- Mandim F, Barros L, Heleno SA, Pires TC, Dias MI, Alves MJ, Santos PF, Ferreira IC. Phenolic profile and effects of acetone fractions obtained from the inflorescences of Calluna vulgaris (L.) Hull on vaginal pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria. Food & Function. 2019; 10: 2399-2407. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31049501

- Zhang T, Liu H, Bai X, Liu P, Yang Y, et al. Fractionation and antioxidant activities of the water-soluble polysaccharides from Lonicera japonica Thunb. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2019. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31739015

- Matthaus B, Ozcan MM. Fatty acid, tocopherol and squalene contents of Rosaceae seed oils. Botanical studies. 2014; 55:48. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5432826/

- Jo MS, Yu JS, Lee JC, Lee S, Cho YC, et al. Lobatamunsolides A–C, Norlignans from the Roots of Pueraria lobata and their Nitric Oxide Inhibitory Activities in Macrophages. Biomolecules. 2019; 9:755. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31757072

- Fu Y, Li F, Ding Y, Li HY, Xiang XR, et al. Polysaccharides from loquat (Eriobotrya japonica) leaves: Impacts of extraction methods on their physicochemical characteristics and biological activities. Int J Biol Macromolecules. 2020. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31923490

- Chu MJ, Du YM, Liu XM, Yan N, Wang FZ, et al. Extraction of proanthocyanidins from chinese wild rice (zizania latifolia) and analyses of structural composition and potential bioactivities of different fractions. Molecules. 2019; 24:1681. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31052148

- Dong LM, Zhang M, Xu QL, Zhang Q, Luo B, et al. Two new thymol derivatives from the roots of Ageratina adenophora. Molecules. 2017; 22: 592. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6154539/

- Zhang ZP, Shen CC, Gao FL, Wei H, Ren DF, et al. Isolation, purification and structural characterization of two novel water-soluble polysaccharides from Anredera cordifolia. Molecules. 2017; 22: 1276. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28769023

- Priolo N, Del Valle SM, Arribere MC, López L, Caffini N. Isolation and characterization of a cysteine protease from the latex of Araujia hortorum fruits. Journal of Protein Chemistry. 2000; 19: 39-49.

- Akihara Y, Kamikawa S, Harauchi Y, Ohta E, Nehira T, et al. HPLC profiles and spectroscopic data of cassane-type furanoditerpenoids. Data in brief. 2018; 21:1076-88. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30450403

- Jordheim M, Calcott K, Gould KS, Davies KM, Schwinn KE, et al. High concentrations of aromatic acylated anthocyanins found in cauline hairs in Plectranthus ciliatus. Phytochemistry. 2016; 128:27-34. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27165277

- Boppre M, Colegate SM. Recognition of pyrrolizidine alkaloid esters in the invasive aquatic plant Gymnocoronis spilanthoides (Asteraceae). Phytochemical Analysis. 2015; 26: 215-225.

- Du YQ, Yan ZY, Chen JJ, Wang XB, Huang XX, et al. The identification of phenylpropanoids isolated from the root bark of Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle. Nat Product Res. 2019: 1-8. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31315448

- El-Tantawy ME, Shams MM, Afifi MS. Chemical composition and biological evaluation of the volatile constituents from the aerial parts of Nephrolepis exaltata (L.) and Nephrolepis cordifolia (L.) C. Presl grown in Egypt. Natural product research. 2016; 30: 1197-201. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26211503

- Matsuda H, Nakashima S, Abdel-Halim OB, Morikawa T, Yoshikawa M. Cucurbitane-type triterpenes with anti-proliferative effects on U937 cells from an egyptian natural medicine, Bryonia cretica: structures of new triterpene glycosides, bryoniaosides A and B. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2010; 58: 747-51. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20460809

- Kisielius V, Lindqvist DN, Thygesen MB, Rodamer M, Hansen HC, Rasmussen LH. Fast LC-MS quantification of ptesculentoside, caudatoside, ptaquiloside and corresponding pterosins in bracken ferns. J Chromatography B. 2020: 121966. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31931331

- Shulha O, Çiçek SS, Wangensteen H, Kroes J, Mäder M, et al. Lignans and sesquiterpene lactones from Hypochaeris radicata subsp. neapolitana (Asteraceae, Cichorieae). Phytochemistry. 2019; 165: 112047.

- Khan WN, Lodhi MA, Ali I, Azhar-Ul-Haq, Malik A, et al. New natural urease inhibitors from Ranunculus repens. J Enzyme Inhibition Med Chem. 2006; 21: 17-19. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16570500

- Neag T, Olah NK, Hanganu D, Benedec D, Pripon FF, et al. The anemonin content of four different Ranunculus species. Pakistan J Pharmaceutical Sci. 2018; 31: 2027-2032. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30393208

- Mabona U, Viljoen A, Shikanga E, Marston A, Van Vuuren S. Antimicrobial activity of southern African medicinal plants with dermatological relevance: from an ethnopharmacological screening approach, to combination studies and the isolation of a bioactive compound. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013; 148: 45-55. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23545456

- You Y, Kim K, Yoon HG, Lee KW, Lee J, et al. Chronic effect of ferulic acid from Pseudosasa japonica leaves on enhancing exercise activity in mice. Phytotherapy Res. 2010; 24: 1508-1513. PubMed: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jf010514x

- Matos P, Figueirinha A, Ferreira I, Cruz MT, Batista MT. Acanthus mollis L. leaves as source of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant phytoconstituents. Natural product research. 2019; 33: 1824-1827. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29417845

- Santos-Rebelo A, Garcia C, Eleuterio C, Bastos A, Castro Coelho S, et al. Development of Parvifloron D-Loaded Smart Nanoparticles to Target Pancreatic Cancer. Pharmaceutics. 2018; 10: 216. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6321128/

- Feng X, Wang X, Liu Y, Di X. Linarin inhibits the acetylcholinesterase activity in-vitro and ex-vivo. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research: IJPR. 2015; 14: 949. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4518125/

- Saini NK, Singha M. Anti–inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic activity of methanolic Tecomaria capensis leaves extract. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012; 2: 870-874. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3609241/

- Aboutabl EA, Hashem FA, Sleem AA, Maamoon AA. Flavonoids, anti-inflammatory activity and cytotoxicity of Macfadyena unguis-cati L. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2008; 5: 18-26. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2816596/

- Park SH, Jang S, Lee SW, Park SD, Sung YY, et al. Akebia quinata Decaisne aqueous extract acts as a novel anti-fatigue agent in mice exposed to chronic restraint stress. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018; 222: 270-279. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29630998

- Guesmi F, Hmed MB, Prasad S, Tyagi AK, Landoulsi A. in vivo pathogenesis of colon carcinoma and its suppression by hydrophilic fractions of Clematis flammula via activation of TRAIL death machinery (DRs) expression. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2019; 109: 2182-2191.

- Chu Z, Wang H, Ni T, Tao L, Xiang L, et al. 28-Hydroxy-3-oxoolean-12-en-29-oic Acid, a Triterpene Acid from Celastrus orbiculatus Extract, Inhibits the Migration and Invasion of Human Gastric Cancer Cells in vitro. Molecules. 2019; 24: 3513. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31569766

- Habtemariam S. The therapeutic potential of Berberis darwinii stem-bark: quantification of berberine and in vitro evidence for Alzheimer's disease therapy. Nat Prod Commun. 2011; 6: 1089-1090. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21922905

- Topolska J, Kostecka-Gugała A, Ostachowicz B, Latowski D. Selected metal content and antioxidant capacity of Sambucus nigra flowers from the urban areas versus soil parameters and traffic intensity. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020; 27: 668-677. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31808083

- Packer J, Naz T, Harrington D, Jamie JF, Vemulpad SR. Antimicrobial activity of customary medicinal plants of the Yaegl Aboriginal community of northern New South Wales, Australia: a preliminary study. BMC Res Notes. 2015; 8: 276. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26122212

- Kim HS, Jang JM, Yun SY, Zhou D, Piao Y, et al. Effect of Robinia pseudoacacia Leaf Extract on Interleukin-1β–mediated Tumor Angiogenesis. in vivo. 2019; 33: 1901-1910. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31662518

- Nawwar M, Swilam N, Hashim A, Al-Abd A, Abdel-Naim A, et al. Cytotoxic isoferulic acidamide from Myricaria germanica (Tamaricaceae). Plant Signal Behav. 2013; 8: e22642. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3745567/

- Patova OA, Smirnov VV, Golovchenko VV, Vityazev FV, Shashkov AS, et al. Structural, rheological and antioxidant properties of pectins from Equisetum arvense L. and Equisetum sylvaticum L. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2019; 209: 239-249.

- Calderon-Montano JM, Martinez-Sanchez SM, Burgos-Moron E, Guillen-Mancina E, Jimenez-Alonso JJ, et al. Screening for selective anticancer activity of plants from Grazalema Natural Park, Spain. Nat Prod Res. 2019; 33: 3454345-8. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29842791

- Pires AS, Rigueiras PO, Dohms SM, Porto WF, Franco OL. Structure‐guided identification of antimicrobial peptides in the spathe transcriptome of the non‐model plant, arum lily (Zantedeschia aethiopica). Chem Biol Drug Design. 2019; 93: 1265-1275.

- Radulovic N, Denic M, Stojanovic-Radic Z. Antimicrobial phenolic abietane diterpene from Lycopus europaeus L.(Lamiaceae). Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010; 20: 4988-4891. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20674349

- Chen X, Li T, Qing D, Chen J, Zhang Q, et al. Structural characterization and osteogenic bioactivities of a novel Humulus lupulus polysaccharide. Food Function. 2020; 11: 1165-1175. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31872841

- Bournine L, Bensalem S, Wauters JN, Iguer-Ouada M, Maiza-Benabdesselam F, et al.. Identification and quantification of the main active anticancer alkaloids from the root of Glaucium flavum. Int J Mol Sci. 2013; 14: 23533-23544. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3876061/

- Basic M, Elgner F, Bender D, Sabino C, Herrlein ML, et al. A synthetic derivative of houttuynoid B prevents cell entry of Zika virus. Antiviral Res. 2019; 172: 104644. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31697958

- Akhtar M, Shaukat A, Zahoor A, Chen Y, Wang Y, et al.. Anti-inflammatory effects of Hederacoside-C on Staphylococcus aureus induced inflammation via TLRs and their downstream signal pathway in vivo and in vitro. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2019; 137: 103767. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31580956

- García ME, Borioni JL, Cavallaro V, Puiatti M, Pierini AB, et al. Solanocapsine derivatives as potential inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase: Synthesis, molecular docking and biological studies. Steroids. 2015; 104: 95-110. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26362598

- Dougnon G, Ito M. Sedative effects of the essential oil from the leaves of Lantana camara occurring in the Republic of Benin via inhalation in mice. J Nat Med. 2020; 74: 159-169. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31446559

- Hsu CL, Fang SC, Yen GC. Anti-inflammatory effects of phenolic compounds isolated from the flowers of Persicaria hydropiperPersicaria hydropiper Zucc. Food & function. 2013; 4: 1216-1222. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23727892

- Ticona LA, SAnchez AR, GonzAles OO, Domenech MO. Antimicrobial compounds isolated from Tropaeolum tuberosum. Natural Product Research. 2020: 1-5. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31913056

- Luis A, Breitenfeld L, Ferreira S, Duarte AP, Domingues F. Antimicrobial, antibiofilm and cytotoxic activities of Hakea sericea Schrader extracts. Pharmacognosy magazine. 2014; 10: S6. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24914310

- Yesilada E, Kupeli E. Clematis vitalba L. aerial part exhibits potent anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive and antipyretic effects. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007; 110: 504-515.

- Amabeoku GJ, Green I, Kabatende J. Anticonvulsant activity of Cotyledon orbiculata L.(Crassulaceae) leaf extract in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007; 112: 101-107. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17398051

- Neuman MG, Jia AY, Steenkamp V. Senecio latifolius induces in vitro hepatocytotoxicity in a human cell line. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology. 2007; 85: 1063-1075.

- dos Santos Alves CF, Bonez PC, de Souza MD, da Cruz RC, Boligon AA, et al. Antimicrobial, antitrypanosomal and antibiofilm activity of Equisetum hyemale. Microbial pathogenesis. 2016; 101: 119-125. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27856271

- Schmidt M, Skaf J, Gavril G, Polednik C, Roller J, et al. The influence of Osmunda regalis root extract on head and neck cancer cell proliferation, invasion and gene expression. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017; 17: 518. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5716017/

- Tian G, Chen J, Luo Y, Yang J, Gao T, Shi J. Ethanol extract of Ligustrum lucidum Ait. leaves suppressed hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Cell Int. 2019; 19: 246. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31572063

- Saddiqe Z, Maimoona A, Abbas G, Naeem I, Shahzad M. Pharmacological screening of Hypericum androsaemum extracts for antioxidant, anti-lipid peroxidation, antiglycation and cytotoxicity activity. Pakistan J Pharmaceut Sci. 2016; 29.

- Tiana C, Yang C, Zhang D, Han L, Liu Y, et al. Antibacterial and antioxidant properties of various solvents extracts of Abutilon theophrasti Medic. leaves. Pak J Pharmaceut Sci. 2017; 30. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28653920

- Ling B, Xiao S, Yang J, Wei Y, Sakharkar MK, et al. Probing the Antitumor Mechanism of Solanum nigrum L. Aqueous Extract against Human Breast Cancer MCF7 Cells. Bioengineering. 2019; 6: 112. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31835887

- Aghajanyan A, Nikoyan A, Trchounian A. Biochemical activity and hypoglycemic effects of Rumex obtusifolius L. seeds used in Armenian traditional medicine. BioMed research international. 2018; 2018.

- Boniface PK, Verma S, Shukla A, Cheema HS, Srivastava SK, et al. Bioactivity-guided isolation of antiplasmodial constituents from Conyza sumatrensis (Retz.) EH Walker. Parasitol Int. 2015; 64: 118-123. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25449289

- Genc Y, Dereli FT, Saracoglu I, Akkol EK. The inhibitory effects of isolated constituents from Plantago major subsp. major L. on collagenase, elastase and hyaluronidase enzymes: Potential wound healer. Saudi Pharmaceut J. 2020; 28: 101-106. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31920436

- Rogozhin EA, Slezina MP, Slavokhotova AA, Istomina EA, Korostyleva TV, et al. A novel antifungal peptide from leaves of the weed Stellaria media L. Biochimie. 2015; 116: 125-132. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26196691

- Ilina T, Kashpur N, Granica S, Bazylko A, Shinkovenko I, et al. Phytochemical Profiles and in vitro Immunomodulatory Activity of Ethanolic Extracts from Galium aparine L. Plants. 2019; 8: 541. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31775336

- Aremu OO, Oyedeji AO, Oyedeji OO, Nkeh-Chungag BN, Rusike CR. in vitro and in vivo Antioxidant Properties of Taraxacum officinale in Nω-Nitro-l-Arginine Methyl Ester (L-NAME)-Induced Hypertensive Rats. Antioxidants. 2019; 8: 309. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31443195

- Jahan S, Azad T, Ayub A, Ullah A, Afsar T, et al. Ameliorating potency of Chenopodium album Linn. and vitamin C against mercuric chloride-induced oxidative stress in testes of Sprague Dawley rats. Environ Health Prevent Med. 2019; 24: 62.

- Parzonko A, Kiss AK. Caffeic acid derivatives isolated from Galinsoga parviflora herb protected human dermal fibroblasts from UVA-radiation. Phytomedicine. 2019; 57: 215-22. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30785017

- Di Sotto A, Di Giacomo S, Toniolo C, Nicoletti M, Mazzanti G. Sisymbrium Officinale (L.) Scop. and its polyphenolic fractions inhibit the mutagenicity of Tert‐butylhydroperoxide in Escherichia Coli WP2uvrAR strain. Phytotherapy Res. 2016; 30: 829-834.

- Di Napoli M, Varcamonti M, Basile A, Bruno M, Maggi F, et al. Anti-Pseudomonas aeruginosa activity of hemlock (Conium maculatum, Apiaceae) essential oil. Nat Prod Res. 2019; 33: 3436-3440.

- Song SY, Hyun JE, Kang JH, Hwang CY. in vitro antibacterial activity of the manuka essential oil from Leptospermum scoparium combined with Tris‐EDTA against Gram‐negative bacterial isolates from dogs with otitis externa. Vet Dermatol. 2019.

- Doukkali Z, Taghzouti K, Bouidida EH, Nadjmouddine M, Cherrah Y, et al. Evaluation of anxiolytic activity of methanolic extract of Urtica urens in a mice model. Behav Brain Funct. 2015; 11: 19. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4423131/

- Farid O, Zeggwagh NA, Ouadi FE, Eddouks M. Mentha pulegium Aqueous Extract Exhibits Antidiabetic and Hepatoprotective Effects in Streptozotocin-induced Diabetic Rats. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Immune, Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders). 2019; 19: 292-301. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30289084

- Bubueanu C, Iuksel R, Panteli M. Haemostatic activity of butanolic extracts of Lamium album and Lamium purpureum aerial parts. Acta Pharmaceutica. 2019; 69: 443-449. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31259737

- Ibrahim AM, Ghoname SI. Molluscicidal impacts of Anagallis arvensis aqueous extract on biological, hormonal, histological and molecular aspects of Biomphalaria alexandrina snails. Experimental Parasitology. 2018; 192: 36-41.

- Fernandez-Martinez E, Jimenez-Santana M, Centeno-Alvarez M, Torres-Valencia JM, Shibayama M, et al. Hepatoprotective effects of nonpolar extracts from inflorescences of thistles Cirsium vulgare and Cirsium ehrenbergii on acute liver damage in rat. Pharmacognosy magazine. 2017; 13: S860. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5822512/

- Sharifi-Rad J, Iriti M, Setzer WN, Sharifi-Rad M, Roointan A, et al. Antiviral activity of Veronica persica Poir. on herpes virus infection. Cell Mol Biol. 2018; 64: 11-17. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29981678

- Li BY, Hu Y, Li J, Shi K, Shen YF, et al. Ursolic acid from Prunella vulgaris L. efficiently inhibits IHNV infection in vitro and in vivo. Virus Res. 2019; 273: 197741.

- Torres-GonzAlez L, Cienfuegos-Pecina E, Perales-Quintana MM, Alarcon-Galvan G, Munoz-Espinosa LE, et al. Nephroprotective effect of Sonchus oleraceus extract against kidney injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion in wistar rats. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity. 2018; 2018: 9572803. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29643981

- Ayaz M, Ahmad I, Sadiq A, Ullah F, Ovais M, Khalil AT, Devkota HP. Persicaria hydropiper (L.) Delarbre: A review on traditional uses, bioactive chemical constituents and pharmacological and toxicological activities. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2019: 112516. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31884037

- Guz L, Adaszek L, Wawrzykowski J, Zietek J, Winiarczyk S. in vitro antioxidant and antibabesial activities of the extracts of Achillea millefolium. Polish journal of veterinary sciences. 2019: 369-376. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31269341

- Mahdavi S, Amiradalat M, Babashpour M, Sheikhlooei H, Miransari M. The antioxidant, anticarcinogenic and antimicrobial properties of Verbascum thapsus L. Medicinal chemistry (Shariqah (United Arab Emirates)). 2019. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31456524

- Oszmianski J, Wojdyło A, Juszczyk P, Nowicka P. Roots and Leaf Extracts of Dipsacus fullonum L. and Their Biological Activities. Plants. 2020; 9: 78. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31936189

- Kim J, Jung KH, Ryu HW, Kim DY, Oh SR, et al. Apoptotic Effects of Xanthium strumarium via PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2019; 2019.

- Shiomi N, editor. Advances in Bioremediation and Phytoremediation. BoD–Books on Demand; 2018.

- Macci C, Peruzzi E, Doni S, Iannelli R, Masciandaro G. Ornamental plants for micropollutant removal in wetland systems. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015; 22: 2406-2415. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24798922

- Augustynowicz J, Lukowicz K, Tokarz K, Płachno BJ. Potential for chromium (VI) bioremediation by the aquatic carnivorous plant Utricularia gibba L. (Lentibulariaceae). Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015; 22: 9742-9748.

- Cui X, Fang S, Yao Y, Li T, Ni Q, et al. Potential mechanisms of cadmium removal from aqueous solution by Canna indica derived biochar. Sci Total Environ. 2016; 562: 517-525. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27107650

- Wechtler L, Laval-Gilly P, Bianconi O, Walderdorff L, Bonnefoy A, et al. Trace metal uptake by native plants growing on a brownfield in France: zinc accumulation by Tussilago farfara L. Environ Sci Pollut Res . 2019; 26: 36055-36062

- Maleva M, Garmash E, Chukina N, Malec P, Waloszek A, et al. Effect of the exogenous anthocyanin extract on key metabolic pathways and antioxidant status of Brazilian elodea (Egeria densa (Planch.) Casp.) exposed to cadmium and manganese. Ecotoxicol Environ Safety. 2018; 160: 197-206.

- Marchand L, Lamy P, Bert V, Quintela-Sabaris C, Mench M. Potential of Ranunculus acris L. for biomonitoring trace element contamination of riverbank soils: photosystem II activity and phenotypic responses for two soil series. Environ Sci Pollut Res . 2016; 23: 3104-3119. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25956517

- Pardo-Muras M, G Puig C, Pedrol N. Cytisus scoparius and Ulex europaeus Produce Volatile Organic Compounds with Powerful Synergistic Herbicidal Effects. Molecules. 2019; 24: 4539. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6943486/

- Salinitro M, Tassoni A, Casolari S, de Laurentiis F, Zappi A, et al. Heavy Metals Bioindication Potential of the Common Weeds Senecio vulgaris L., Polygonum aviculare L. and Poa annua L. Molecules. 2019; 24: 2813. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31374997

- Guo X, Wang P, Li Y, Zhong H, Li P, et al. Effect of copper on the removal of tetracycline from water by Myriophyllum aquaticum: Performance and mechanisms. Bioresource Technol. 2019; 291: 121916. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31377514

- Noori A, Zare Maivan H, Alaie E, Newman LA. Leucanthemum vulgare Lam. crude oil phytoremediation. Int J Phytoremediation. 2018; 20: 1292-1299. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26121329

- Yu X, Brown JM, Graham SE, Carbajal EM, Zuleta MC, Milla-Lewis SR. Detection of quantitative trait loci associated with drought tolerance in St. Augustinegrass. PloS one. 2019; 14. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31671135

- Alur HH, Pather SI, Mitra AK, Johnston TP. Evaluation of the gum from Hakea gibbosa as a sustained-release and mucoadhesive component in buccal tablets. Pharmaceutical development and technology. 1999; 4: 347-358. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10434280

- Keshari AK, Srivastava R, Singh P, Yadav VB, Nath G. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized by Cestrum nocturnum. J Ayurveda Integrative Med. 2018.

- Hussain N, Abbasi T, Abbasi SA. Generation of highly potent organic fertilizer from pernicious aquatic weed Salvinia molesta. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018; 25: 4989-5002. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29209963

- Balsamo RA, Willigen CV, Bauer AM, Farrant J. Drought tolerance of selected Eragrostis species correlates with leaf tensile properties. Ann Botany. 2006; 97: 985-991.

- Zhou Y, Lambrides CJ, Kearns R, Ye C, Fukai S. Water use, water use efficiency and drought resistance among warm-season turfgrasses in shallow soil profiles. Functional plant biology. 2012; 39: 116-125. PubMed: https://www.publish.csiro.au/fp/FP11244

- Baracho NC, Vicente BB, Arruda GD, Sanches BC, Brito JD. Study of acute hepatotoxicity of Equisetum arvense L. in rats. Acta Cirurgica Brasileira. 2009; 24: 449-453. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20011829/

- Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM, Lambie BS, Wilkins GT, Schep LJ. Poisonous plants in New Zealand: a review of those that are most commonly enquired about to the National Poisons Centre. N Z Med J. 2012; 125: 87-118. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23321887

- Bregnbak D, Menné T, Johansen JD. Airborne contact dermatitis caused by common ivy (Hedera helix L. ssp. helix). Contact Dermatitis. 2015; 72: 243-244. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25630853

- Pour BM, Sasidharan S. in vivo toxicity study of Lantana camara. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011; 1: 230-232. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3609184/

- Botha CJ, Lessing D, Rösemann M, Van Wilpe E, Williams JH. Analytical confirmation of Xanthium strumarium poisoning in cattle. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2014; 26: 640-645. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25012081